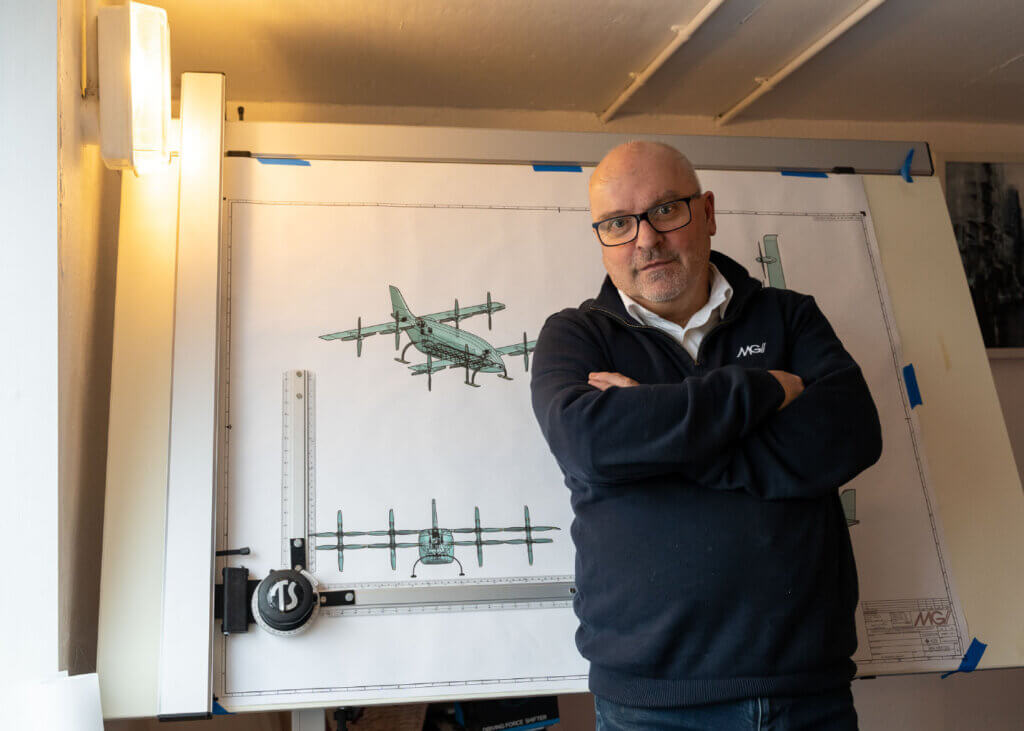

For anyone who followed Formula One (F1) racing in the nearly three decades from 1989 onward, Mike Gascoyne will need no introduction. Gascoyne graduated from the University of Cambridge in engineering fluid mechanics and subsequently left the Ph.D. program to take up a key position as head of aerodynamics at McLaren.

In the next 27 years, he continued to make his mark in F1 with a range of leading roles from technical director to chief designer at top-tier teams, including Tyrell, Jordan, Renault, and Toyota. His last direct involvement in F1 was setting up the Lotus Caterham team from the ground up in 2009 through his consultancy company, MGI Engineering Ltd., that he established in 2003.

Leaving F1 in 2015, Gascoyne continued in his role at MGI Engineering with the aim of bringing F1 technology to the wider engineering world — not limited to automotive applications.

This is how MGI Engineering’s work intersects the aerospace domain, and on April 19, 2023, the company unveiled its UAV technology demonstrator: the Mosquito. Vertical reached out to Gascoyne to get more insight on his move into the eVTOL space.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Alex Scerri: Mike, can you give us some background on how MGI Engineering is working to enter the cargo UAV market?

Mike Gascoyne: At MGI Engineering, we quickly saw that our work was becoming increasingly aerospace-focused, especially with the need for lightweight composite structure designs. We saw that aerospace composite technology had not evolved at the same pace as F1, so we leveraged our competitive drive which led us to do a lot more aerospace work.

We met Stephen Fitzpatrick of Vertical Aerospace, who acquired MGI Engineering and for two years traded as Vertical Advanced Engineering. Two years ago, I bought the company back and now we are an independent consultancy with a cadre of engineers — the senior members of the team all having over 20 years’ experience in F1.

We have been concentrating on eVTOL and aerospace for the last four to five years. As part of that process, we launched the technology demonstrator program that we unveiled last month to showcase our capabilities in leading design and consultancy to the eVTOL market.

Alex Scerri: Do you have any plans to have your own UAV/eVTOL vehicle or will you focus on providing your services to other original equipment manufacturers (OEMs)?

Mike Gascoyne: That’s a very good question. For now, we are still focused on providing our services to other OEMs, but we are also open to developing our own products if there is a suitable investment partner. We could continue to develop our demonstrator program to the stage of a commercial vehicle. It’s not something we will do on our own, but with the right investment and partner, it’s a possibility.

Alex Scerri: During the unveil event, you showed two versions of the Mosquito demonstrator. Is your design team developing these in parallel or are you inclined to choose one design?

Mike Gascoyne: The key is that the elements of the design configuration are interchangeable — the tiltwing and independent tiltrotor, as well as the coaxial rotor design. The final configuration would be set together with the operator. We are taking examples from the automotive world, which we know well, by using common platforms, powertrains, battery modules, etc. This is vital to establish. Although it is a nascent technology, at some point, these vehicles will be produced in numbers that has not been done in aerospace before. Adopting efficient automotive design and production principles is essential.

Alex Scerri: What is behind the name of the demonstrator: the Mosquito?

Mike Gascoyne: It’s always difficult to pick a name that hasn’t been used before. If you look at the de Havilland Mosquito aircraft from World War II, it was not only a beautiful aircraft per se, but its wooden monocoque and plywood construction was a precursor of how we use composite materials today. As the power density of batteries still isn’t very good, and not improving at the rate we had hoped, keeping the structure as light as possible is even more critical. This is why I believe coming from F1 and being familiar with composite design techniques gives us an edge in this business.

Alex Scerri: You are also focusing on scalability when it comes to payload capability.

Mike Gascoyne: Exactly. The technology demonstrator is essentially a subscale prototype for larger vehicles. However, it is already at a size where it can be commercially viable. We already see a demand for vehicles of this size for applications such as mail and medical supply delivery. This current smaller version can be developed very quickly from demonstrator to prototype to commercial vehicle, and it can be scaled up to a vehicle with a payload of up to 500 kilograms (1,102-pounds).

Alex Scerri: You are concentrating your efforts on a cargo version to start. Is it because you see a quicker path to certification and commercialization compared to passenger eVTOLs?

Mike Gascoyne: There is a lot of focus on the glamorous side of the eVTOL market — air taxi applications. That is where a lot of investor money is going. In some way, the industry is trying to fly before it can walk. Passenger eVTOL will come after the successful deployment of cargo eVTOL, based on hundreds of thousands of flying hours of autonomous cargo flights. There is a huge potential for this type of operation if, for example, you look at the islands around the U.K., Greece, etc.

I was recently at an event in Monaco and was speaking with H.S.H. Prince Albert. I told him that during the Monaco Grand Prix, the bay will be full of yachts, and each one will need to be continuously resupplied by a fleet of gasoline powered tenders. Most trips will be for small deliveries of groceries from the supermarket and that could easily be done now with small, fully electric aircraft.

Ship-to-ship and ship-to-shore transfers is a market that exists already. The other advantage is that most of the flight time will be over non-urban areas, which means minimal risk to third parties while gaining experience and collecting data to improve the technology.

These operations can start today as you don’t need any new infrastructure, whereas if you want to fly people from Heathrow to Central London, you need vertiports at both ends and the vehicles must meet stringent safety criteria for passenger flight.

Alex Scerri: Another technology that is being honed in F1 is hybrid power. Is this something you plan to exploit as well?

Mike Gascoyne: At the moment, we’re looking at battery-only power for the technology demonstrator. Of course, you can start looking at hybrid versions to extend range while carrying a useful payload. It is a reasonably straightforward second step. As a start, we’ll focus on battery power to get us up to the 100-kilometer (62-mile) range. When people talk about a 200-km (125-mi) range, then you are going to struggle to get anywhere near that with these vehicles. That is where hybrid power could be needed, so that’s the approach we are taking.

Alex Scerri: Some eVTOL startups appear to struggle when they face the arduous path to certification compared to the impetus of the initial design phase. Does your experience with the complex world of F1 regulations help you at all?

Mike Gascoyne: There are two things to consider. In F1, you do have a lot of regulations, especially for safety tests that you must pass. The way F1 does it is interesting because they have no prescriptive way of doing anything. They just give you a test you’ve got to pass, whether it is a crash test or whatever. They review and improve those requirements every year based on the feedback from any incidents that may occur, but essentially, you are free to design the lightest and most aerodynamically efficient structure possible. That drives innovation.

In the aerospace world, the rate of change is much slower so you might have a certifiable vehicle, but it will be not commercially viable because it will be too heavy. You must balance the two requirements. We have that agile development background from F1, but we also worked in aerospace for the past 10 years and have parts currently flying on the Airbus A320neo and Bombardier C-Series. We are very aware of the issues around certification and the balance between innovation and certifiability.

Alex Scerri: Thereare a few companies that are looking into eVTOL racing concepts. How useful is this to the industry and is it something you would consider with your background?

Mike Gascoyne: It is something we thought about and sketched some things out. There could be a market for a single-seat sports utility vehicle. If you look at something like Extreme E and the extreme environments they race in, doing that in a single-seat eVTOL could be very interesting. You could see a vehicle like this having a real market in that more lightly regulated space and could even help in the general development of eVTOL. Of course, it comes at some risk because as with automotive racing and extreme sports, you could have some consequences.

Alex Scerri: Do you have any other thoughts to share with the eVTOL and UAV community?

Mike Gascoyne: As in my message at the EVER Monaco 2023 conference, I don’t think anyone can have any doubt on the size of the market and value predictions for this industry. At the same time, we cannot underestimate the challenges of getting there. As an engineer, some of the timeframes that people are talking about appear very optimistic.

We have moved on from making aircraft out of bamboo and canvas, and we have over 100 years of aviation experience behind us. It took just half a century from the Wright Flyer to the Concorde, and with its experience, MGI can certainly aspire to design the Concorde of eVTOLs.