In the early 1940s, as the Second World War raged overseas, many individuals and companies in the U.S. were feverishly attempting to design and perfect a rotary-wing aircraft. Most famously, Sikorsky Aircraft, based out of Bridgeport, Connecticut, was leading the charge with its VS-300 prototype, which first took flight in 1939.

One of the lesser-known companies among this vanguard movement was Higgins Industries, Inc., owned by Andrew Jackson Higgins. While much of the early rotorcraft development in the U.S. took place in the Northeast, Higgins based his company in New Orleans, Louisiana. His ambition was to design and fly a light two-place helicopter with side-by-side seating. His attempts to do so have not been fully documented by authors in early helicopter publications.

Born on Aug. 28, 1886, in Columbus, Nebraska, Higgins became a successful businessman and boatbuilder. The Second World War industrialist owned one of the largest boatbuilding companies in the world, and his Higgins LCVP (Landing Craft Vehicle, Personnel) boats became a major asset to the war effort and played a crucial part in the amphibious D-Day landings in Normandy in June 1944. The landing craft was capable of carrying 36 soldiers and hauling military vehicles and equipment.

“Andrew Higgins is the man who won the war for us,” President Dwight Eisenhower told historian Stephen Ambrose in a 1964 interview. “If Higgins had not designed and built those LCVPs, we never could have landed over an open beach. The whole strategy of the war would have been different.”

In 1942, Higgins created Higgins Aircraft, with the intent of building airplanes for the U.S. military. He planned to manufacture Curtiss-Wright C-76 Caravans and Curtiss C-46 Commando transport aircraft, but the U.S. military cancelled the contracts in early August 1944, with just a few aircraft completed.

Launching the EB-1

Higgins was well aware of the work of Igor Sikorsky and his VS-300 and R-4 two-place helicopters for the U.S. Army Air Forces. He believed the helicopter would have a strong future in the aviation industry, and decided that he wanted to be a part of it. With that, Higgins formed a new Helicopter Division, and hired Enea Bossi to design his Higgins Helicopter.

Bossi was attached to the Isaac Delgado Trade School in New Orleans, which became a part of Higgins Industries, Inc. in 1943. When all Higgins Aircraft contracts were cancelled the following year, Higgins put all his efforts into completing his experimental EB-1 helicopter. His objective was to sell this helicopter to the U.S. Army Air Forces.

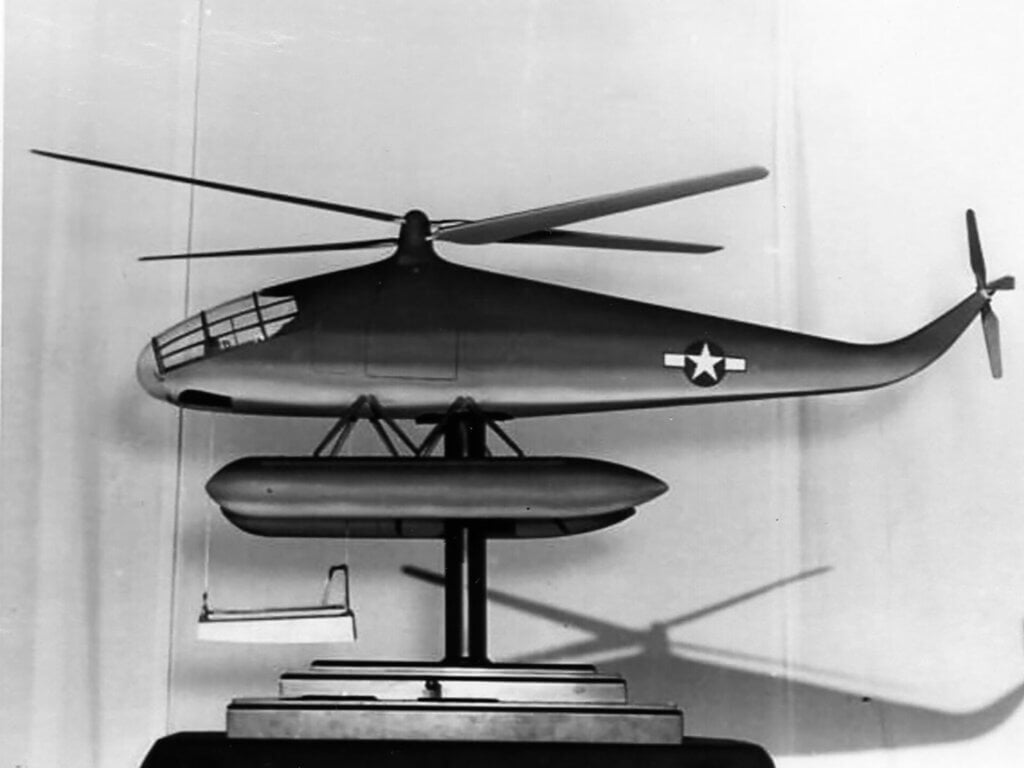

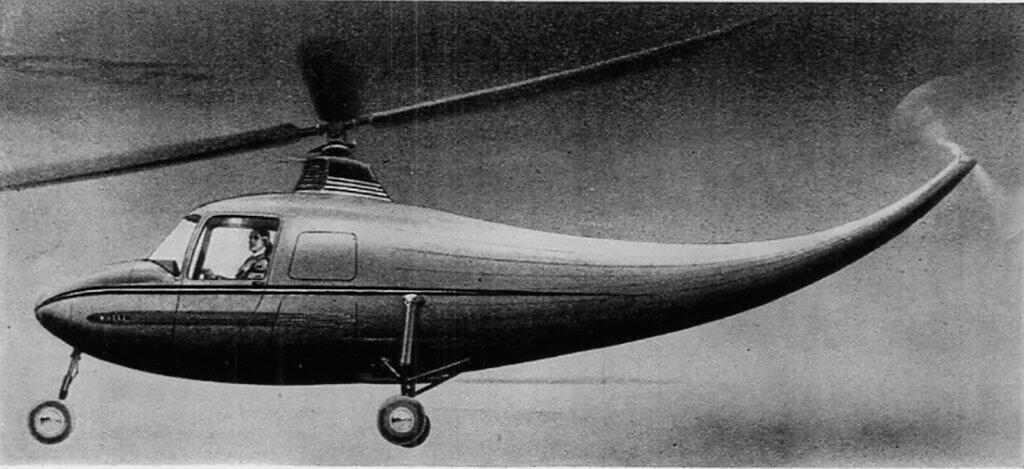

Bossi completed plans for the EB-1 (the “EB” of the aircraft’s type designation were from his initials), and began construction of the prototype. The two-place helicopter was similar to Sikorsky’s R-4, with a four-bladed main rotor and two-blade tail rotor at the end of the fuselage. The main rotor consisted of two two-bladed rotors with one a few inches higher in the main rotor hub than the other, and its diameter was 32 feet (9.75 meters). The helicopter was powered by a Warner 180-horsepower seven-cylinder radial engine with pressure cooling, placed behind the helicopter’s two-place cabin. The EB-1 had metal skin covering its main cabin, including the engine area. The rear fuselage and tail was fabric-covered.

The aircraft’s controls were on the left side, and they resembled those of a fixed-wing aircraft. The instrument panel was standard, with a wheeled control column including pitch-control and clutch-control levers, along with rudder pedals.

The first prototype helicopter had a small tail assembly at the back of the fuselage to help prevent the tail rotor from contacting the ground. The fixed landing gear was in a tricycle configuration, with a single wheel in the front and two wheels at the back near the engine.

The EB-1 had an empty weight of 1,951 lb. (885 kg), with a gross weight of 2,546 lb. (1,155 kg).

Historical documentation is minimal on the actual flying of the prototype — and even who piloted it during aerial tests. The EB-1’s first flight was in 1943, but only one aircraft was ever completed. Further tests resulted in changes to the end of the fuselage with the tail rotor canted up. This led some to comment that the EB-1 resembled a scorpion.

A short test program

The aircraft’s cruise speed was estimated to be 120 mph (200 km/h). A free-wheeling unit allowed the helicopter to go into autorotation should the engine fail. Later in flight testing, the fuselage was changed and straightened out.

As testing continued on the two-place EB-1 helicopter, Higgins engineers were hard at work designing larger versions of the helicopter. Higgins had plans to commercially manufacture his helicopter in the two-place version, as well as a larger 14-passenger airliner. His engineers were also designing a four-place twin-engine version of the EB-1, and Bossi had even designed and made plans for an amphibious version.

Over time, work stopped on the development of the Higgins EB-1. In the end, Higgins was unable to interest anyone in either a commercial or military version of the type. While Bossi received a patent for the EB-1 on Aug. 14, 1945, Sikorsky, Bell, Kaman, Piasecki, and Hiller were already becoming major players in establishing a commercial and military rotary-wing industry in the U.S. by this point.

Andrew Higgins passed away in New Orleans on Aug. 1, 1952, at the age of 65. His pioneering helicopter dreams were never accomplished, but his EB-1 did fly. He and many other innovative pioneers in the early days of helicopter development played a major part in the rich history of helicopters in the U.S. Higgins may not be well known for his involvement in early helicopters, but he will always be remembered for the vital contribution his landing craft made to the Allies’ success in the Second World War.