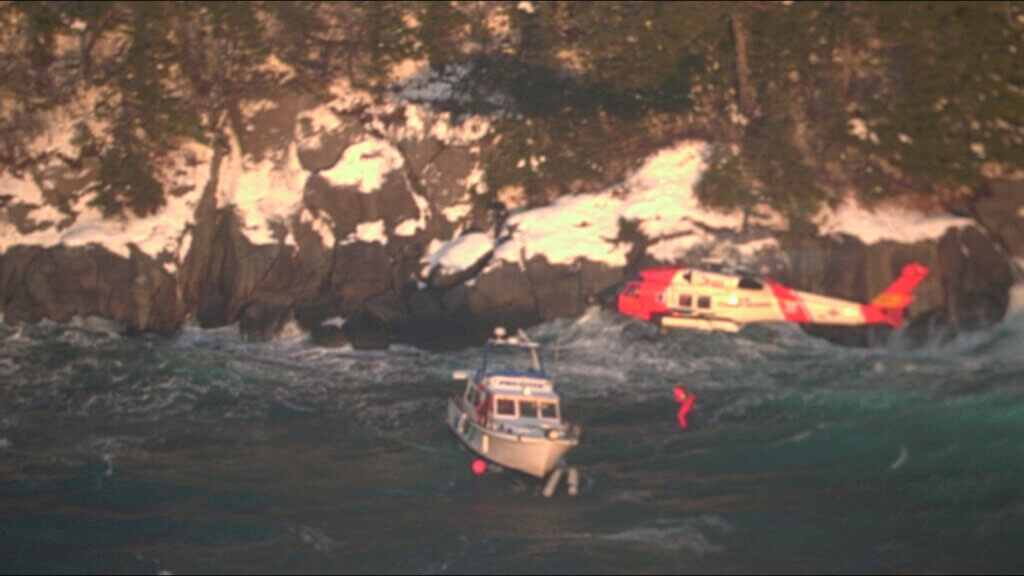

It was a cold, windy afternoon near Whittier, Alaska, and the deck of the disabled fishing boat Privateer was slick with ice. Waves tossed the anchored vessel near the rocky shore of Esther Island as a much smaller Sea Tow vessel maneuvered to throw it a line. Several previous attempts had failed, but this one was looking more promising. Overhead, the crew of the U.S. Coast Guard Sikorsky MH-60T Jayhawk orbiting the scene were beginning to doubt that they would be needed.

“Most of us have seen this scenario before, and 999 out of 1,000 times it’s a really good outcome where the vessel is taken under tow and everyone’s safe and happy,” said LT Eric Bonomi, who was flying co-pilot on the mission from the left seat. In the back of the cabin, AMT2 Hunter Beaudoin, the flight mechanic, had also mentally shifted gears. Beaudoin had departed Air Station Kodiak that morning with the expectation of performing his first operational hoist, but now that seemed unlikely. “We’re just here to support, but most likely we’re not doing anything on this case,” he recalled thinking.

The crew heard over Channel 16 — the maritime radio distress frequency — that the tow line was finally secure and holding. The Sea Tow captain instructed the Privateer to release the anchor line. For a very short period of time, everything seemed to be under control. Then the radio erupted in chaos.

“We heard some frantic voices calling out that the tow line had snapped, that the vessel was adrift and headed for the rocks,” said Beaudoin, who remembers a split second of silence on board the aircraft as the news sunk in. Bonomi doesn’t recall the exact words the Sea Tow captain shouted into his radio as he watched the Privateer being swept away by the waves and current. But he said it was something to the effect of: “Coast Guard, you’ve got to do something!”

The last frontier

Kodiak is around 260 miles (420 kilometers) as the crow flies away from Esther Island, or roughly the width of the state of Utah. That’s not especially close in any context other than Alaska, which spans around 2,400 mi. (3,860 km) from its eastern boundary to the western tip of the Aleutian Islands. The Coast Guard maintains two air stations in Alaska to provide aerial search-and-rescue (SAR) support over this vast territory. One of them is Air Station Sitka, which covers the southeastern panhandle. The other is Air Station Kodiak, which covers everything else.

The Coast Guard has 15 aircraft based in Kodiak, including six MH-60T Jayhawks, four Airbus MH-65D Dolphins, and five Lockheed Martin HC-130J long-range surveillance planes. Only slightly smaller than Hawaii’s Big Island, Kodiak Island is the largest island in the Gulf of Alaska and well positioned to support shipping traffic in the northern Pacific. But air crews stationed here routinely range all over the state: from Dutch Harbor (or Unalaska), 600 mi. (970 km) down the Aleutian chain, to Barrow (or Utqiagvik), nearly 1,000 mi. (1,600 km) to the north.

“Our area of responsibility up here is very large,” said LCDR Abigail Wallis, who was the aircraft commander (AC) for the Whittier rescue. “So, you come in for duty and you may be gone for a week because you get launched on some crazy case all the way down in Dutch Harbor or up in Barrow.”

Vast distances aren’t the only challenges that air crews have to contend with in Alaska. There’s also the weather, which regularly presents extreme winds, icing, and reduced visibility. Rugged mountain ranges create downdrafts and turbulence, and Alaska’s northern latitudes mean winter days as short as six-and-a-half hours in Kodiak, with no daylight at all farther north. Infrastructure of all types — refueling facilities, weather reporting stations, cell service — is often limited or nonexistent.

For pilots, Bonomi said, “Kodiak is the varsity flying in the Coast Guard. A lot of other units will deal with one or two of the challenges that we deal with on a daily basis in isolation. But all together is really where things get hard.” All Coast Guard pilots assigned to Kodiak are qualified aircraft commanders, but they must fly as co-pilots until they complete an Alaska AC syllabus, spanning a full winter.

As is the case at all Coast Guard air stations, air crewmembers have ancillary duties that keep them busy when they’re not flying. But they tend to do a lot of flying — and when they’re not deployed on operational missions, they’re often training. According to LT Scott Kellerman, an MH-60T pilot who is the air station’s standardization training officer and a unit flight examiner, helicopter crewmembers typically stand four to five 24-hour SAR duties per month and do two training flights per duty cycle if no calls come in. These can include practicing day and nighttime hoists to vessels, cliff rescues, inland search techniques and, when conditions allow, rescues in heavy surf.

Timing is everything

Wallis, Bonomi, and Beaudoin were actually preparing to launch on a local training flight on the morning of Dec. 12, 2022, when the Privateer sent out a distress call. “The initial report was that the three [people] on board were going to be abandoning ship and swimming to the shoreline, which is always a risky evolution just based on the water temperatures,” Wallis said. “And that day in particular, there were very rough winds and high seas.”

Chief aviation survival technician David McClure, who graduated from rescue swimmer school in 2005 and now spends most of his time supervising other swimmers, was standing the “dog watch” that day — an eight-hour gap created by the misalignment between weekend and weekday duty cycles. “Normally if I was doing the case I would have passed it off to one of the younger guys,” he said. “This day when we got launched it was just one time when there was no one around and they were already ready to go, so I went with [them].”

In addition to the Jayhawk, the Air Station launched a C-130, which flew ahead and provided a weather report. Although there was widespread cloud cover between Kodiak and Whittier, the C-130 crew reported that the clouds topped out at 8,000 feet (2,440 meters) and were broken at the destination, with enough gaps to permit a safe descent. That gave Wallis and Bonomi the confidence to climb to 10,000 feet (3,050 meters) for the transit, allowing them to fly directly to the scene in cold but clear conditions, rather than picking their way through the coastal terrain beneath the clouds.

The C-130 crew established contact with the Privateer and learned that two of the three people on board were incapacitated, further complicating the rescue effort. The Jayhawk crew had plenty of time to discuss their options during the two-and-a-half-hour flight from Kodiak. “We ran through a bunch of different scenarios on . . . how we were going to accomplish the mission,” McClure recalled. By the time they arrived at Esther Island, however, the commercial Sea Tow vessel was also on scene, and the Privateer had opted to attempt a tow first. So the Jayhawk set up a holding pattern in the steady northwest winds of around 40 knots (75 km/h).

“Every time we would come over the boat we were facing into the direction of where the wind was coming from, so that in the event we needed to we could make an immediate approach to the water to help out,” Wallis said. And that’s exactly what they did when the tow line parted and the vessels radioed for urgent assistance. The Privateer was then around 25 yards or meters from the shoreline, moving parallel but ever closer to the rocks.

“Typically we do sort of a forward and right motion when we’re hoisting with the cutter or boats because the boat would be underway,” Wallis explained. “In this particular instance the boat was drifting backwards because the wind was pushing it, and so that meant that I was going to have to come backwards as I’m hoisting.” Because Wallis couldn’t see the boat when she was over it, she had to rely on Beaudoin for conning commands to keep her in the correct position. And because the cliffs of the rocky coast jutted out behind the aircraft, Beaudoin and Bonomi were constantly keeping an eye on their clearance.

Meanwhile, McClure was lowered to the icy deck of the Privateer and determined that all three people onboard could be brought up via quick strop, a simple harness that is typically the fastest method for evacuating ambulatory survivors. McClure rode with one survivor up the hoist, then was lowered back to the boat and brought up another. “And then on the way back out to pick the third guy up, the first guy got my attention and was like, ‘Hey, there’s a dog in the boat,’” McClure recalled. “And my initial thought was, ‘How am I going to get this dog out of the boat, too?’”

conditions are challenging and/or obstacles pose a risk of collision. LT. Scott Kellerman, U.S. Coast Guard Photo

Fortunately, that turned out to be easier than expected. “For the situation that it was in, [the dog] was probably the calmest person on the boat,” observed McClure. He put the last survivor in the quick strop, wedged the medium-sized dog in halfway, and told the survivor to hold on tight. “They hoisted us up . . . Hunter was able to grab the dog and toss him into the cabin, and then we were able to get the last survivor in,” McClure said. Even before they were safely on board, the Privateer had smashed into the rocks.

“That was a very eye-opening sight to see that as they’re still dangling below the helicopter,” said Beaudoin, whose first hoist rescue was one for the ages.

“The timing of everything worked out perfectly,” said Wallis, pointing out that rescue missions rarely come down so close to the wire. “Had the call come in 10 minutes later or we had to go all the way around Whittier or we had even been in a different part of our circle overhead, it may not have gone quite as smoothly.”

Going the distance

One month later, a medevac illustrated the opposite extreme of what air crews can face in Kodiak: ultra-long-distance missions that extend over multiple days.

On Jan. 10, 2023, Scott Kellerman and his co-pilot, LCDR Ian Sibberson, were forward deployed in Cold Bay on the Alaska Peninsula when they received a report that a crewmember aboard the tanker ship FPMC 33 had broken both of his legs. But the ship was still around 660 nautical miles (1,220 km) south of Dutch Harbor in the Aleutians, which was itself around 155 nm (290 km) from Cold Bay. Typically, the maximum range for an overwater rescue in the Jayhawk is around 225 nm (415 km) to enable adequate fuel reserves and time on station.

The tanker ship expected to be within range for a rescue about 24 hours later. Kellerman and Sibberson elected to reposition to Dutch Harbor that afternoon so as to be ready, which wasn’t as simple of a decision as it might seem. For one thing, they had to line up hangar space, which Kellerman said “is vital in the winter, because you leave an aircraft outside, it turns into a popsicle and you’re not going to get it for another couple of months.” Once they found an available hangar, they had to coordinate with the other occupants to fit the Jayhawk inside.

“Everywhere else I’ve been [stationed], we’ve never even bothered trying to get hangar space — we just do the work outside,” Sibberson observed. “You kind of have to make friends with people in a town you’ve never been to and ask them nicely for hangar space, and then sometimes they have to move their aircraft out of the hangar so you can get in. . . . The people in Alaska are usually really, really good about supporting us.”

The following day, Jan. 11, was windy but clear. As the tanker ship approached the eventual rendezvous point, a C-130 launched out of Kodiak to establish initial communications with the vessel and review hoist procedures in order to minimize the helicopter’s time on scene. Kellerman and Sibberson launched out of Dutch Harbor along with their flight mechanic, AMT1 Alex Morris, and rescue swimmer, AST1 Paul Mills.

“We took off with a fair amount of gas just to give ourselves a buffer,” Kellerman said, noting that the helicopter was close to its power limits while hoisting. But the hoist operation itself went smoothly. Mills descended to the deck of the tanker, assessed the patient, called for a rescue litter to be sent down, and then packaged the patient in the litter for retrieval. Within half an hour, Mills and the patient were onboard the helicopter and en route to Dutch Harbor, where the patient was transferred to a fixed-wing air ambulance for transport to Anchorage.

Kellerman acknowledged that such protracted SAR cases can be physically and mentally draining for everyone involved. But he also relishes the complex flight planning that is routinely demanded of Coast Guard air crews in Alaska, who must overcome myriad challenges to accomplish their missions safely.

“From a professional aviator standpoint, you’re using all your brainpower to figure out a good solution,” he said. “It’s rewarding . . . when the planning comes together and we do what we say we’re going to do and it works out.”