Engaging with community leaders and citizens and creating a workable infrastructure are important steps in the development and acceptance of eVTOL aircraft, according to numerous speakers at the Vertical Flight Society’s 17th annual Electric Aircraft Symposium in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, from July 22 to 23.

“Community acceptance is one of the biggest challenges we face,” said Rex Alexander, president of Five-Alpha, an aeronautical consultancy specializing in helicopter, vertical lift and eVTOL infrastructure.

Alexander led the four-speaker community integration discussion panel on July 22. “A lot of people say, ‘I’d really like to fly that eVTOL, but don’t you dare put a vertiport in my backyard.’ That [issue] is something we are going to have to address,” he said.

Another challenge for eVTOL acceptance is separating truth from fiction, said Clint Harper, an advanced air mobility (AAM) community advocate.

“There is a lot of misinformation and misunderstanding out there,” Harper said. “A lot of the work I’ve done is to get away from the flying cars [narrative] and bring the conversation back to aviation to help the community understand” what the AAM sector and eVTOL aircraft are about.

Harper said the communities’ concerns of noise, emissions and accessibility are easily resolved. “I’ve noticed after engagement a change in attitudes,” Harper said.

Starr Ginn, AAM strategist for NASA Armstrong Flight Research Center who has specialized in vehicle technology, asked the audience the primary question: “How do we make all this work?”

Among its numerous projects, the center is involved in helping develop a framework for AAM operations.

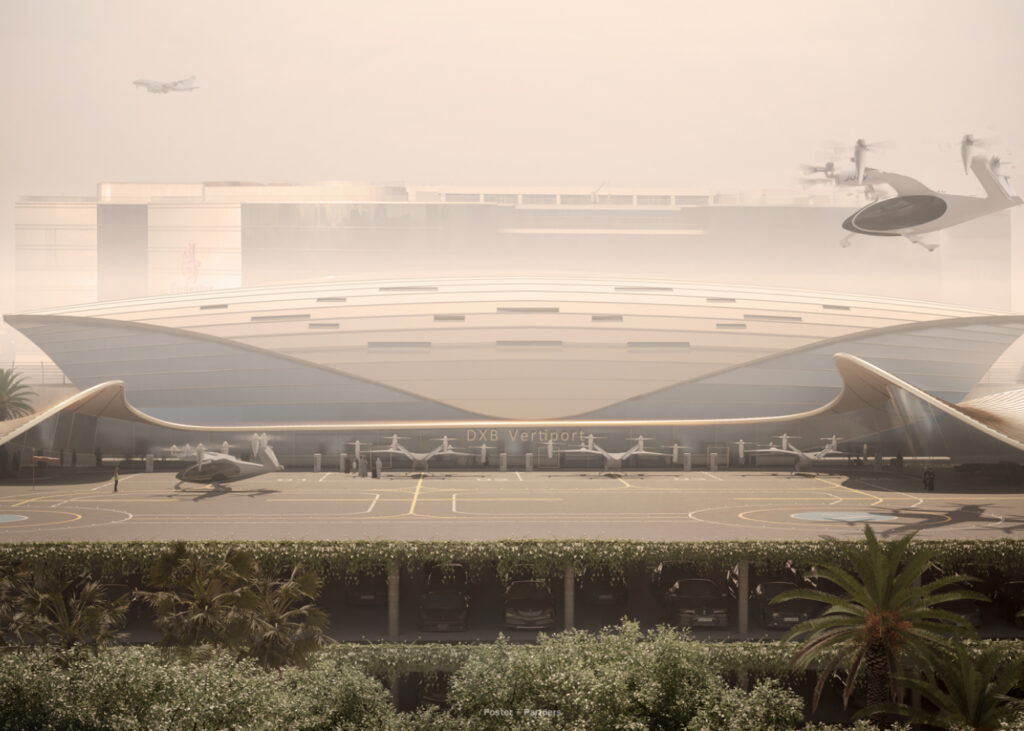

Ginn said one concern is the infrastructure needed to charge these electric aircraft quickly at various vertiports scattered through numerous communities. “These operations need to be more rapid,” she said. “For people to make money [with these aircraft], you need to think of this like a hub-and-spoke operation.”

Ginn said it doesn’t make sense for eVTOL operators to spend millions of dollars on these vertiports “until you get the community buy-in. This is the last, but most important piece that we must concentrate on.”

A general aviation airport is tolerable because the aircraft noise is intermittent, but human factors research, which examines various characteristics of users and the jobs and systems in which they work, revealed that communities might not tolerate a vertiport operation with aircraft landing constantly, Ginn said.

Grant Fisk, co-founder of Volatus Infrastructure, which connects communities of the future with eVTOL technology, stressed the transformational nature of eVTOL.

“This is a technology that will transform peoples’ lives the same way the [Ford] Model-T did,” Fisk said. “This kind of infrastructure will need to be accessible for everyone today. It needs to be a flexible, scalable solution so we can integrate from day-one operations” in various sized communities.

When the panel pivoted to questions from symposium attendees, panel moderator Yolanka Wulff, executive director of the Community Air Mobility Initiative (CAMI), led off with a question to NASA’s Ginn on what the realistic cadence of eVTOL operations might look like.

Ginn answered that NASA looked at shrinking down needed airspace for eVTOL aircraft to initiate a safe instrument flight rules (IFR) procedure, which, at present, is around 32 by 24 nautical miles of airspace at any given airport, a big area for a high cadence operation.

“We looked at shrinking that down to two to four nautical miles of airspace, basically 500 feet before you start your descent,” Ginn said. “We’re trying to cut down the time you’re up in the airspace and get you down as quickly as possible.”

In terms of cadence, “you’re really restricted on the size of operations by how much area you have to park and charge aircraft,” Ginn explained. Utlitizing existing infrastructure and portable charging stations is an initial solution, she said.

eVTOL operations could be limited initially. The average heliport may see a dozen operations in a month, said panelist Harper, and nighttime operations may be prohibited.

“From a public acceptance, we’re giving [communities] something they’ve never seen before,” Harper reminded.

Despite the public acceptance challenge, Fisk said there is community excitement around eVTOL aircraft, particularly when compared to helicopters.

“People see [eVTOL] operations as not as disruptive. They see this as quieter, easier for communities to digest,” Fisk said. “There is a lot of education that we will have to provide, but there is already excitement that we can build on.”

Alexander added a footnote: “Before we educate the community, we have to educate community leaders to carry the message for us.”

CAMI, as part of its Urban Air Policy Collaborative Program, runs a nine-week course for public agency and airport staff that covers the broad aspects of AAM from the aviation perspective, infrastructure, multi-modal integration planning and zoning, rules and responsibility.

Another question during the panel discussion dealt with eVTOL stakeholders starting eVTOL operations. Most heliports are for private use, and as such, the pathway to eVTOL operations may not be that difficult.

“From that perspective, you’re not dealing with airport authorities and department of transportations,” Harper said. “Because it is privately held land, you’re dealing with city and land use planners. They are seeing how well the use that you have for that land is integrated into the surrounding lands.”

eVTOL operators should remain flexible, said the panelists. Most communities see heliports as an industrial use item, which limits where they can place their AAM operation. If the business plan calls for numerous destinations from, for example, a city center, the operator will have problems because most downtown areas aren’t zoned for industrial uses.

“That is something, you will have to work through with your city planners,” Harper said.

The panelists were then asked about the various uses of these electric-powered AAM aircraft, beyond the air taxi concept.

“The use case question is almost as important as how and where we are going to develop them,” Alexander said. “Because this is all about revenue. There will be a lot of use cases defined by private business and private ownership.”

Alexander said airborne emergency medical services (EMS), organ transport and tourism are other use cases for these electric-powered aircraft.

Fisk, who has talked to various hospitals about AAM air service, offered this cautionary note on EMS: “Hospitals are very real estate restricted. Getting a heliport on a hospital is a challenge on any given day.”