This is not a sexy story.

A sexy story, as Staff Sgt. Emmett Spraktes explains in his self-published book The Selfish Prayer, is a story like the one he tells from July 17, 2009, when he found himself treading air 25 feet above a lethal firefight in the Watapur Valley of eastern Afghanistan. A California Highway Patrol officer who had been deployed as a flight paramedic with the California National Guard’s C Company, 1-168th General Aviation Support Battalion (a medevac, or DUSTOFF, unit), Spraktes was on his way down to assist a group of injured soldiers when the UH-60 Black Hawk hoist he was attached to momentarily jammed, leaving him as a dangling target.

Before a passing bullet could strike him, the line came unstuck, and Spraktes dropped to the ground. There, he tended to the most severely wounded soldier in the group, and then four others, as the remaining members of his crew repeatedly braved fire to lift the casualties to safety. (“By the grace of God we were not hit,” copilot Chief Warrant Officer Scott St. Aubin later remarked. “I have no idea how you miss a giant Black Hawk helicopter.”) Spraktes was awarded the Silver Star for his actions that day, while his three fellow crewmembers received the Distinguished Flying Cross with Valor Device.

A sexy story from the battlefield has drama. It has fates decided by a few centimeters’ difference in a bullet’s trajectory, and human beings performing magnificently under almost unimaginable duress. It is, in other words, a story of luck and courage — the type of story that has played out all too often over the more than 12 years that the United States and its allies have been involved in the War in Afghanistan, and that has been told numerous times on the pages of this magazine, and many others.

But this story, and the one that Spraktes ultimately chose to tell in The Selfish Prayer, is a different type of story. It is a story that emerged in U.S. Army DUSTOFF operations in Afghanistan not from a handful of extraordinarily heroic actions, but from mundane statistics collected from 671 patient transfers. It is a story driven by data rather than drama; a story in which courage and luck play a small role, and training and experience play a large one.

It is, quite possibly, the most significant DUSTOFF story of the entire war.

Inventing an Industry

Although the U.S. Army used helicopters extensively for medical evacuation during the Korean War, DUSTOFF (which stands for “Dedicated Unhesitating Service To Our Fighting Forces”) properly dates to 1962, when the Army’s 57th Air Ambulance Detachment deployed to South Vietnam. In the Korean War, most medical evacuations had been conducted in Bell H-13 Sioux helicopters, a variant of the Bell 47. These minimally powered, three-seat helicopters were far from optimal for the medevac role, and most patients were carried on external litters without a medical attendant. By contrast, the 57th’s larger, more powerful Bell UH-1 Huey helicopters allowed patients to be carried in the cabin, with room for additional crewmembers. This created a new demand for Army flight medics, who came to their role after completing a basic training course at the Army Medical Training Center in Fort Sam Houston, Texas.

Over the course of the Vietnam War, DUSTOFF helicopters moved an estimated 850,000 to 900,000 allied military personnel and Vietnamese civilians. Many DUSTOFF crews did not survive the experience. According to the Army’s DUST OFF: Army Aeromedical Evacuation in Vietnam, medevac helicopters were 3.3 times as likely to be shot down as all other helicopters in the war, and more than a third of medevac pilots and crewmembers became casualties in their work. But, at the end of the war, some of those who did make it home brought their experience to bear in a new civilian air ambulance industry in the U.S., one largely inspired by the Army model. And that industry exploded. Today, an estimated 400,000 patient transports are conducted by helicopter annually in the U.S. alone. According to the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), the nation currently has 75 air ambulance companies, which operate more than 800 helicopters between them.

Arguably, the U.S. helicopter air ambulance industry, which has been under considerable scrutiny from the FAA and National Transportation Safety Board in recent years, may still be suffering negative safety consequences from the aggressively mission-oriented attitude of many ex-Vietnam pilots, who shaped the industry’s early culture. If flight safety remains a perennial concern for the sector, however, the medical side of the business has advanced dramatically over the past four decades. Although U.S. air ambulance operators vary widely in their aircraft, equipment, and training standards, the standard of medical care they offer is generally quite high. Civilian air ambulances are routinely staffed by critical care-trained flight nurses and paramedics, most of whom have extensive pre-hire experience, and a mandate for continuing education. They operate using formalized protocols and standardized patient care documentation, often under physician direction.

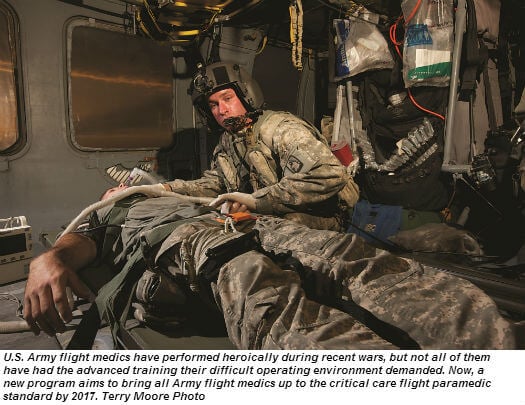

Meanwhile, in the Army, the medevac mission transitioned from the Huey to the Sikorsky UH-60 Black Hawk, which first entered service with the Army in 1979. But not much else changed. In stark contrast to the increasing medical sophistication of civilian air ambulance crews, training standards for Army combat medics remained at a level equivalent to the Emergency Medical Technician– Basic certification. There was no standard continuing education requirement beyond maintaining this EMT-B level of proficiency, and medics who were not deployed often went months without seeing a patient.

The growing gap between military and civilian flight medic standards did not go entirely unnoticed. However, it wasn’t until the War in Afghanistan that it was perceived as a real problem — and one with unacceptable consequences.

A Different Kind of War

If there’s a prototype for the post-Cold War battlefield story, it’s probably Black Hawk Down, Mark Bowden’s account of the 1993 Battle of Mogadishu that has become so deeply embedded in the popular consciousness, many people don’t know the events it describes by any other name. Army Lt. Col. (Dr.) Robert Mabry, who was a sergeant first class at the time, was a Special Forces medic during the Battle of Mogadishu, and a member of the Combat Search and Rescue team that fast-roped down to the site of Super 61, the first Black Hawk that crashed during the battle. Inspired, in part, by those events in Somalia, Mabry went to medical school and became an emergency room doctor. In 2005 and 2010, he deployed to Afghanistan as a physician with Special Forces.

Although the medevac model that emerged during the Vietnam War was considerably more advanced than its predecessor in Korea, the basic idea was the same: namely, load up the wounded, and fly them to surgical facilities as quickly as possible. “The transport times were short,” explained Mabry. “There wasn’t any expectation that [the medics] would do any advanced medical procedures.” The relatively brief, targeted conflicts of subsequent decades didn’t give the Army a compelling reason to change the model, which is why the training standards for its flight medics also remained unchanged.

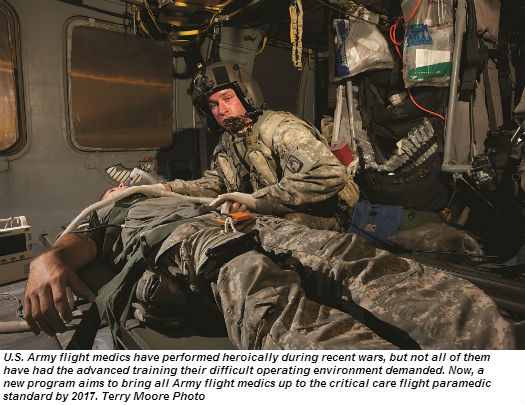

But the War in Afghanistan was different. In this graveyard of empires, much of the action was taking place in remote canyons near the eastern border with Pakistan, or in the country’s expansive southern deserts — far from the U.S. military’s main surgical facility at Bagram Air Field. This encouraged widespread deployment of forward surgical teams, who frequently performed urgent interventions on critical trauma patients before handing them over to DUSTOFF for transfer to Bagram. As Mabry quickly discovered, however, caring for these fragile, post-operative patients was simply beyond the capabilities of many Army flight medics, particularly on flights that could last more than an hour.

“I would intubate people, and hand them over to these medics who were just overwhelmed,” Mabry recalled. “I was putting extremely sick people on these helicopters, and sometimes I would have to hop on board and fly with them to the combat hospital.” Once at Bagram, it could take days for Mabry to arrange return transportation, resulting in prolonged absences from the forward operating base where he was most needed.

Mabry was frustrated. “I knew what the civilian standard was,” he said. “I had to ask, ‘Why are we doing it this way?’”

Mabry wasn’t the only one questioning the status quo. In California, key players in the National Guard had already recognized deficiencies in the Army medevac system, and made considerable progress in bringing C Company, 1-168th GASB (“Charlie Company”) up to a civilian standard. Charlie Company’s initial deployment to Afghanistan, in 2002, reinforced its conviction in the value of advanced training and qualifications, and it spared no effort in preparing for its second deployment, in December 2008. By the time Charlie Company shipped overseas, nearly two-thirds of its medics were qualified paramedics — many of whom, including Spraktes, had years of real-world experience through their civilian roles. Even its crew chiefs were trained to the EMT-B level, the same certification required of active-duty Army flight medics.

One person who was heavily involved in these preparations was CW2 Jason Penrod, whose Nevada National Guard unit was a detachment of Charlie Company. Penrod, a Reno native, was already a civilian flight paramedic when he enlisted as a medic in the National Guard in 1994. In 2000, he was accepted into flight school, going on to become a UH-60 instructor pilot. He also continued his progression in the medical field, completing his doctor of pharmacy training in 2005.

Like other paramedics with civilian experience, Penrod had noticed the shortcomings of the Army medevac system almost immediately. “I could see pretty quickly that the training for the flight medic was sorely lacking,” he said. “They didn’t know what they didn’t know.” When he learned he would be deploying to Afghanistan with Charlie Company, he recognized an opportunity to back up his observations with scientific evidence. Penrod decided that he would do a retrospective study on Charlie Company’s deployment, comparing its patient outcomes with outcomes for patients transferred by traditional medevac units. He worked with Sgt. Mike Ferguson, another Charlie Company paramedic, to design a computerized system for capturing data from patient care reports — although he wasn’t quite sure how he would capture data from other medevac units.

Halfway through Charlie Company’s deployment, the unit was approached by U.S. Air Force Col. Warren Dorlac, a Joint Theater Trauma System Director who had noticed a significant improvement in mortality since Charlie Company’s arrival. “He wanted to know, why had survivability of patient outcomes changed so appreciably in a positive direction?” Penrod recalled. Dorlac connected Penrod with Dr. Mabry, who was immediately interested in Penrod’s study. Mabry realized that the data Penrod needed for comparison could come from the Joint Theater Trauma Registry (JTTR), a database maintained at the U.S. Army Institute of Surgical Research that contains key patient information for more than 60,000 combat trauma cases from Iraq and Afghanistan since 2001.

Mabry and Penrod crunched the numbers after Charlie Company returned to the States. Although many trauma system studies use onemonth outcomes as a basis for comparison, most of the patients transported by DUSTOFF were Afghan nationals, and no mechanisms existed to obtain data for these patients once they left the military system. Instead, the study used 48-hour mortality to identify early deaths that might have been prevented by advanced pre-hospital or inflight interventions. The final study population consisted of 671 patients who were transported by air ambulance to military hospitals in southern and eastern Afghanistan between December 2007 and March 2010. Of these patients, 469 were transported by standard medevac units, and 202 were transported by Charlie Company. The analysis showed that Charlie Company’s model was associated with a 66 percent lower estimated risk of mortality when compared with standard Army medevac units — a difference so dramatic, it surprised even the study’s authors.

“I was expecting maybe 15 percent, something like that,” Mabry said, describing the 66 percent reduction as “huge.” The results were presented to the Army in 2011, and published in the Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery in 2012. Now the Army had to decide what to do about them.

The Path to Reform

Long before the study with Charlie Company was published, Mabry and others had argued forcefully — and ineffectively — for improvements to the Army’s medic training standards. The subject was a highly charged one, as Spraktes describes in The Selfish Prayer. “The idea that there was a problem significant enough to cause the deaths of soldiers on the field was a bitter pill to swallow,” he writes, noting that challenges to the medevac system were often construed as personal attacks, not only on the leaders of the system, but also, most emotionally, on the flight medics.

Yet it’s a grave misreading of its authors’ intentions to see the Charlie Company study as a condemnation of medics themselves. “It’s certainly not their fault,” Penrod emphasized. “These guys are just in way over their heads when it’s time to pick up that first patient.” In his book, Spraktes notes that the turnover rate for active-duty flight medics has been “astronomical” over more than a decade of war, and writes, “They were asked to shoulder tremendous stress, yet they were not adequately prepared for what they faced. Many do amazing work in terrible situations without the consolation that the Army has given them enough advanced training to make a difference. It’s been a travesty.”

Some units took the initiative to improve their own standards of training. For example, after Charlie Company took over medevac duties from the 101st Airborne Division in late 2008, the 101st decided that it, too, needed to raise the bar, and sent all of its flight medics to civilian paramedic training prior to their next deployment. Meanwhile, in theater, Dorlac recommended that enroute critical care nurses be mobilized to supplement standard medevac crews after Charlie Company left. The first of these nurses arrived in Afghanistan in 2010, although “that was really just a band-aid solution,” Penrod explained. Not only did the nurses deploy without a physician medical director or standardized patient care protocols, many of them came to DUSTOFF directly from a hospital environment, with little, if any, experience in giving care in the back of a noisy helicopter. “It was a big adjustment for most of them,” said Penrod.

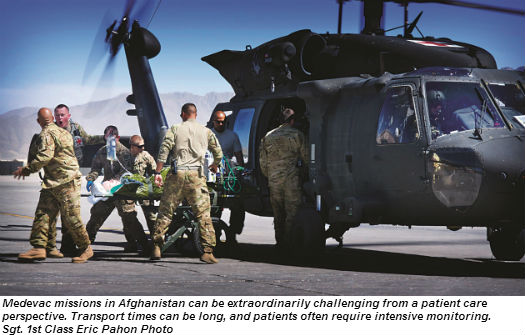

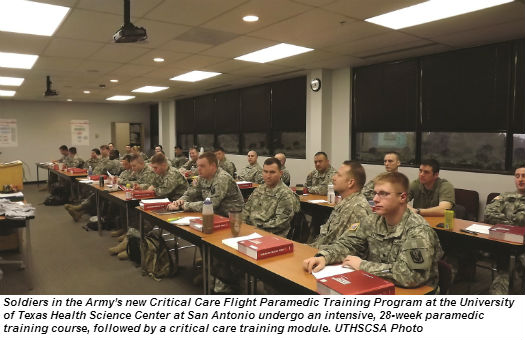

With the completion of the Charlie Company study, the Army was forced to admit that these piecemeal reforms simply weren’t enough. In 2011, the Surgeon General of the Army directed the organization’s medical department to develop a program to train Army flight medics to the critical care flight paramedic level; shortly thereafter, the first of two pilot programs was launched at the University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio (UTHSCSA). The pilot programs proved successful, and in 2013, the Department of Defense awarded a five-year, $8 million contract to UTHSCSA to continue the training, part of a plan to bring all Army medics up to the new standard by 2017.

According to Dr. Lance Villers, associate professor and chair of the Department of Emergency Health Sciences at UTHSCSA, soldiers in the Critical Care Flight Paramedic Training Program undergo an intensive, 28-week paramedic training course modeled on the accelerated courses that are often provided to civilian firefighters. “It’s intense,” he said. “It’s the same amount of training that we may do over a full year in a more traditional civilian academic environment.”

Afterward, the soldiers undergo a critical care training module that includes 80 hours of classroom instruction and 200 hours of clinical experience, with a focus on caring for the most critically ill and injured patients.

The creation of the Army’s Critical Care Flight Paramedic Training Program has been an enormous achievement for the people who fought to improve the system. Significant as it is, however, that milestone is not the end of this story. Being a flight paramedic “is not like riding a bicycle,” said Penrod, “it’s a perishable skill.” With the War in Afghanistan now winding down after 13 long years, the Army will have to find creative ways to ensure that its newly minted paramedics receive the skills practice they need to maintain their proficiency. “The sustainment is a huge piece that we really want to make sure we get right,” said Mabry.

Here, the civilian helicopter air ambulance industry may be able to contribute to the cause. Productive civilian-military training partnerships already exist through initiatives like the Air Force’s Centers for the Sustainment of Trauma and Readiness Skills (CSTARS), which provide Air Force medical personnel with the opportunity to train alongside civilian trauma specialists prior to their deployment to combat theaters. In fact, from 2007 until his retirement from the Air Force in 2011, Dorlac was the director of one of these centers, at UC Health University Hospital in Cincinnati, Ohio (see p.58, Vertical, Oct-Nov 2013). UC Health’s CSTARS has significantly expanded its rotary-wing training component over the past year, in part through ride-alongs with UC Health’s Air Care & Mobile Care, which operates Airbus Helicopters EC145s. More such partnerships could be a way to strengthen productive collaboration between the civilian and military worlds, in addition to providing Army medics with a way to keep their skills sharp.

“I think the military air ambulance system definitely needs to interface more with the civilian air ambulance system,” said Mabry, mentioning that he’s open to ideas from civilian readers of Vertical. He added, “If we get in a homeland defense scenario, this is going to have huge implications for interoperability.”

According to Villers, the soldiers who have been through the Critical Care Flight Paramedic Training Program at UTHSCSA thus far have proven to be more than equal to their demanding training, with pass rates for their paramedic and flight paramedic certification exams approaching 100 percent. “These are not easy exams,” said Villers. “[The soldiers’] motivation and success has been fantastic.” And it is hard to imagine that any soldier who fully appreciates the significance of the training could not be extraordinarily motivated. Many soldiers become flight medics with the dream of performing heroic battlefield rescues; of proving themselves, as Spraktes did, in the presence of real, gut-wrenching fear. Yet a life saved is a life saved, and lives are saved just as surely through appropriate intubations and superior patient monitoring as through more obvious acts of courage.

“Unfortunately,” said Penrod, “there have been a lot of soldiers who paid with their lives to demonstrate the difference in that standard of care.”