How high is the potential risk from released droplets by infectious patients for the helicopter crew? Do pathogens spread from the cabin into the cockpit? These questions are not only highly relevant during the coronavirus pandemic: transporting patients with highly infectious diseases like influenza, tuberculosis or meningococcus is also playing an increasingly great role at DRF Luftrettung. Back in the autumn of 2019, DRF Luftrettung addressed this topic and started a scientifically-accompanied field test in cooperation with the German consulting centre for hospital epidemiology and infection control (BZH) in Freiburg. The findings from this study enable initial conclusions about transmission pathways to be drawn, which the hygiene management team at DRF Luftrettung can use to build on.

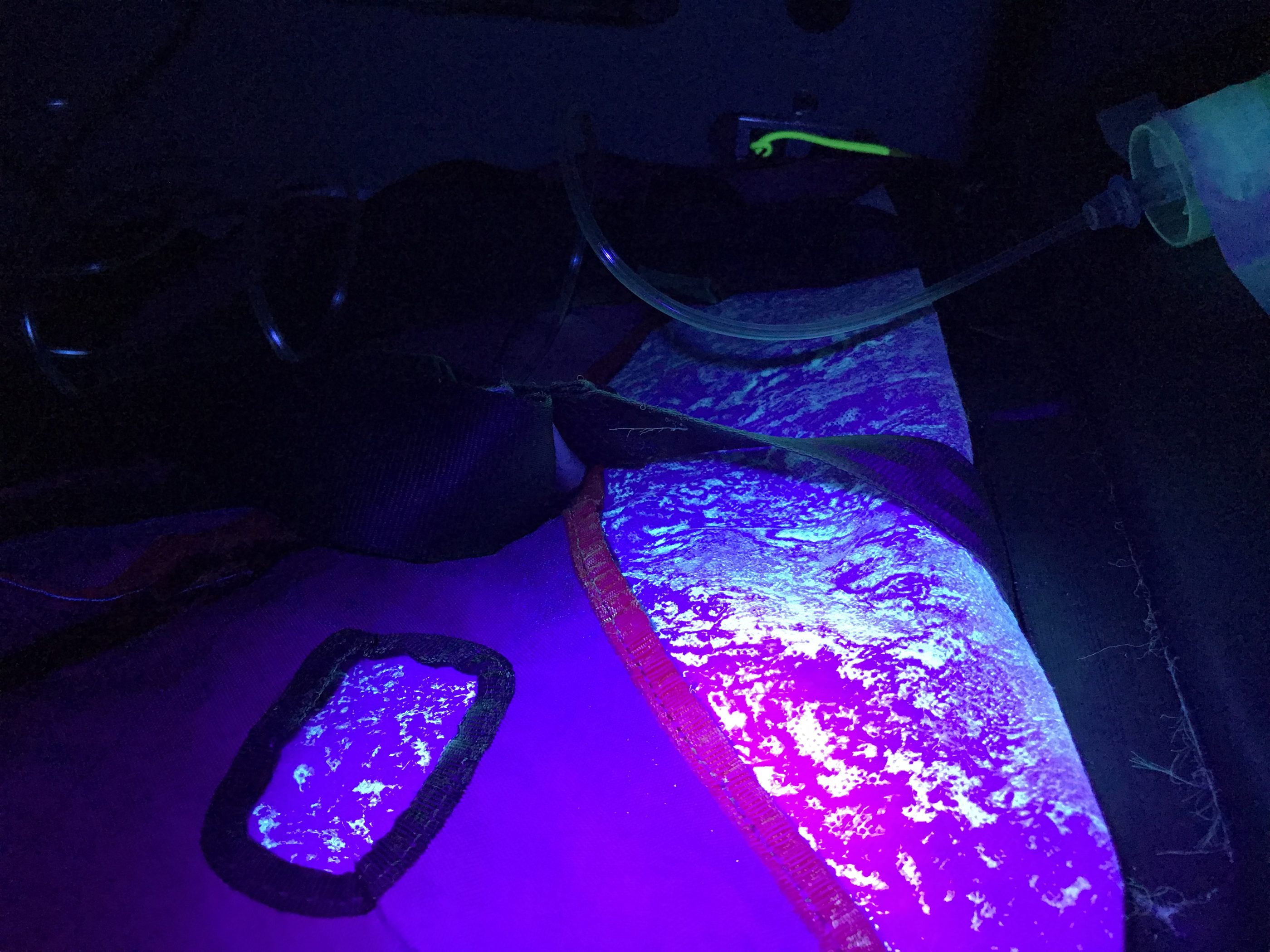

Within the scope of the project, a total of 16 test runs were performed on board the H145 and the EC135, 11 of which were on the ground and five in the air. Two scenarios were essentially depicted, and diversified within the course of the study. One of these was a worst case scenario, simulating a major pathogen release, and the other depicted an alternating, less extreme pathogen release. An oxygen nebuliser level with the patient’s head was used to recreate the droplets being released. The test simulated a droplet release like that which would occur if the spontaneously breathing patient or person coughed or sneezed in the cabin, as well as on the basis of the (intentional or accidental) disconnection of a breathing tube. Air flows were detected by means of fluorescence, and thus also the movements of the droplets. Their spread was made visible with UV light. The tests were carried out both with and without a curtain dividing cabin and cockpit in order to be able to draw conclusions about if and to what extent pathogens spread into the cockpit from the cabin.

Generally speaking, the tests indicated that with a spontaneously breathing patient there is a risk of pathogens not only spreading in the cabin, but also in the cockpit. The probability of infection depends on various factors like the type of pathogen, the transmission pathway and the exposure time. In the worst case scenario, i.e. a massive emission of droplets, there was a high probability of the pathogens not just settling on the surfaces in the entire cabin, but also spreading to the cockpit if there is no dividing curtain.

In the presence of a curtain, the particles landed on it. During the second test, with a short droplet emission which is equivalent to a cough or brief separation from a breathing tube in real life, there were deposits around the patient but not in the cockpit. This implies that the duration of droplet release determines the range and the degree of contamination. Variables such as ventilation settings for heating or air conditioning, flight direction or flight manoeuvres were also taken into consideration.

These findings enable various measures to be derived regarding patient and occupational protection. It is crucial to clean all surfaces in the cabin after transporting a highly infectious patient, because the restricted space obviously increases the risk of contamination in comparison to a normal hospital room. Separating the cockpit and the cabin can generally also provide additional protection. Medical crews absolutely must wear personal protective equipment.

“The hygiene management team at DRF Luftrettung has set itself the goal of optimizing the already high hygiene standards in emergency medicine above and beyond the legal guidelines. This was also where the idea for the scientifically-accompanied field test came from. At the start of the study, we could not have predicted that the topic would be quite so explosive in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, but it makes the importance of our work even clearer,” said Raimund Kosa, coordinator of hygiene management at DRF Luftrettung, who played a key role in supervising the project with support from the BZH. The project was accompanied by DRF Luftrettung’s Scientific Working Group, which supports research ideas and projects that contribute towards optimizing air rescue, among other things.

In the course of the coronavirus pandemic, DRF Luftrettung has implemented extensive measures to protect its staff and patients. These include the mandatory use of personal protective equipment and the strict hygiene measures at the HEMS bases, as well as increasing training courses on hygiene for crew members. In addition, 11 EpiShuttles have been procured. These special segregated stretchers provide optimal protection for both the patients and the crew. The stations which have this equipment will also be ready for action more quickly after each operation, as the very time-consuming disinfection of helicopters after missions with highly infectious patients will no longer be necessary. The patient lies under a transparent cover and can be connected to an intensive respiratory device via air-tight access points while being monitored and treated at the same time.

The scientifically-accompanied field test forms the basis for further hygiene management work at DRF Luftrettung. Aside from cockpit separation, another aspect affects alternative disinfecting technologies, because until now, there has not been any procedure that is approved by aircraft manufacturers on account of avionics and the diversification of technical components.