A recent investigation by the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) determined that a servo flap failed before the catastrophic in-flight breakup of a K-Max helicopter, but neither the manufacturer, Kaman, nor the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) has issued guidance on how to prevent such failures in the future.

Pilot Tom Duffy was killed when his helicopter came apart during firefighting operations in Pine Grove, Oregon, on Aug. 24, 2020. An experienced pilot flying for his family’s company, Montana-based Central Copters, Duffy had more than 2,000 hours of flight experience in K-Max helicopters at the time of the crash.

First certified by the FAA in 1994, the K-Max has a unique intermeshing rotor system, featuring twin counter-rotating, two-bladed rotor systems mounted side-by-side on individual pylons. A single transmission normally keeps the blades of each rotor system 90 degrees out of phase with the other’s and the pylons are tilted to allow the blades to clear the opposing rotor hub.

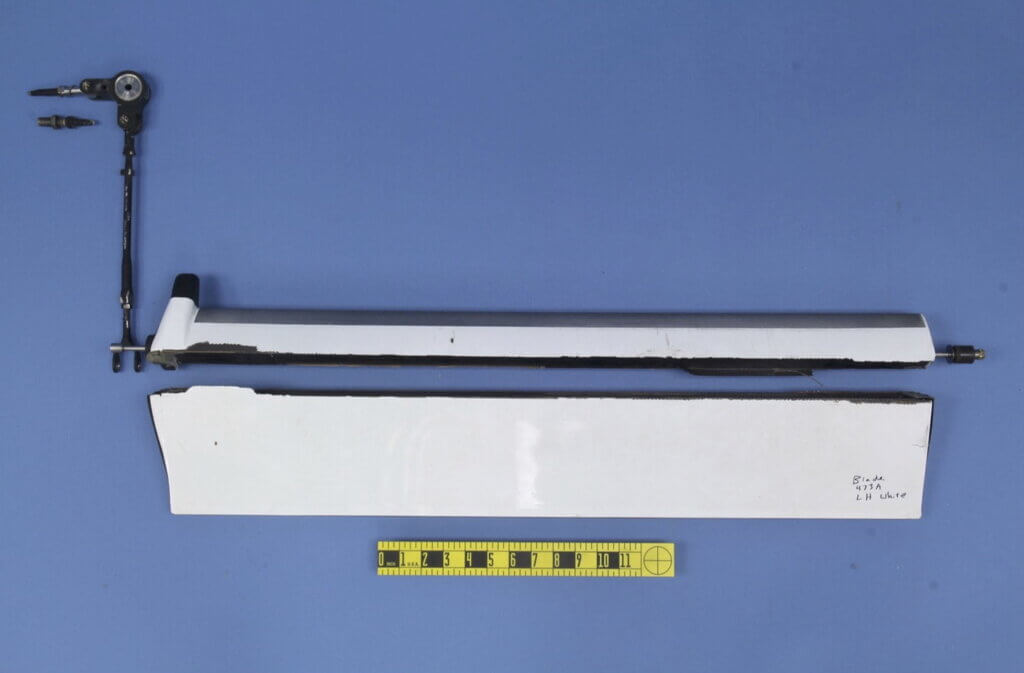

Control of the blades is accomplished through servo flaps, small airfoils mounted on the trailing edge of each blade around three-quarters of the way to the tip. The pilot’s flight control inputs are transferred through rods to the servo flaps, which deflect the airstream to twist the rotor blades and change their pitch.

Because the pilot is only moving the servo flaps, the required forces are relatively small. That allows the aircraft — which has a maximum gross weight of 12,000 pounds (around 5,440 kilograms) with external load — to be flown without hydraulic assistance.

In the Oregon crash, NTSB investigators determined that a crack in one of the left rotor system’s servo flaps grew progressively, ultimately leading to the separation of the flap’s afterbody — the panels attached to the spar that form the airfoil shape. This resulted in a loss of control of the associated left blade.

The NTSB concluded that the left rotor blades then struck the right rotor blades, causing the in-flight separation and breakup of the left blades. At the time, Duffy was hovering at around 140 feet over a river, filling the water bucket attached to his long line. The helicopter rolled to the left as it descended and impacted the river.

Investigators were unable to determine why the servo flap failure ultimately resulted in a collision between the left and right rotor systems. They said it was likely that flight control inputs, including the pilot’s responses to an abnormal vibration in the rotor system, were a factor in the catastrophic outcome, but the lack of flight data precluded analysis of the control inputs leading up to the collision.

The NTSB noted that in 2009, the same helicopter (then operating under a different registration) experienced an event in which an entire servo flap separated from its attachment brackets while in flight, but the pilot was able to land the aircraft safely.

However, the agency also called attention to another accident involving a K-Max operated by Woody Contracting in Donnelly, Idaho, on June 16, 2010. Pilot Roy Kettle had been lifting a large log using a 200-foot long line when two of the helicopter’s counter-rotating blades collided with each other, causing a crash that resulted in Kettle’s death.

Investigators for that accident were likewise unable to determine the reason for the collision, but found that the afterbody had separated from the servo flap on one of the left rotor blades.

There is industry speculation that something similar might have happened in the crash of a Black Tusk Helicopters K-Max in Killam Bay, British Columbia, on Oct. 4, 2021. Pilot Gary Weber was killed when his helicopter impacted the water while carrying logs over the bay. That accident is still under investigation by the Transportation Safety Board of Canada (TSB), but docket material for the Central Copters crash indicates that TSB representatives examined that wreckage last June for “comparative analysis” to the Black Tusk crash.

Vertical submitted multiple questions to Kaman, including whether the company has issued any new guidance to operators as a result of either crash or has plans to do so in the future. A Kaman spokesperson said the company was unable to comment due to the ongoing investigation. When asked whether the FAA plans to issue an airworthiness directive for K-Max helicopter blades, a spokesperson said via email, “We don’t have anything to report at this time.”

Meanwhile, the family of Tom Duffy has sued Kaman in U.S. District Court, contending that “a defectively designed, manufactured, and marketed servo flap on the blades of his K-Max helicopter caused the crash” and that the 2020 crash was “substantially identical to a previous accident about which Kaman had knowledge.”

Kaman denied the allegations, initially claiming instead that Duffy “negligently operated the K-Max helicopter,” and that Central Copters failed to adequately maintain the aircraft, and/or failed to adequately train and supervise Duffy. However, both parties agreed to the dismissal of Kaman’s counterclaims on May 19.

The K-Max is a niche helicopter designed for repetitive heavy-lift operations, and just 60 aircraft were made across two production runs. After ceasing initial production in 2003, Kaman decided to restart the line in 2015. Yet, the company announced earlier this year that it was discontinuing the K-Max, citing “low demand and variation in annual deliveries, coupled with low profitability and large working capital inventory requirements.”

Kaman said it would continue to support the existing K-Max fleet in operation, but further investment in product improvement seems unlikely. In 2019, the company announced a program to design and certify all-composite rotor blades for the K-Max, which still relies on rotor blade spars made from Sitka spruce. The all-composite blades never materialized, though, and Kaman declined to comment on the status of the program.