A Universal Helicopters Newfoundland and Labrador LP Bell 407 makes its way through the remote Torngat Mountains National Park in northern Labrador. Mike Reyno Photo

In 1952, mining magnate Lang Hancock and his wife Hope boarded their single-engine Auster and flew from Nunyerry to Perth, Western Australia; a route they had flown many times before. Only, on this particular occasion, poor weather caused Hancock to alter his course, and in the process history was made. They took a sheltered route along the Turner River, and as they flew low, out of the weather, Hancock saw something he’d never noticed before — the walls of the gorge looked like solid iron, red and rusted and towering above the river. That day, Hancock discovered the world’s largest iron deposit, the commodity which would hold up the country’s economy for decades to come and make Hancock one of the world’s richest men.

Half a century later, stories of spotting world class mineral deposits from the air are seen as tales of a bygone era; satellite imagery and geophysical surveys provide geologists with a plethora of detailed data, all of which can be viewed, interpreted and manipulated from behind a desk. However, while a concept can be generated remotely, the reality is that no mineral deposit can truly be “discovered” until it is sampled.

Pre-2008, when the mining industry was booming, helicopters were used extensively to support mapping campaigns in inaccessible locations, particularly within Canada, Australia and South America. However, cost cuts across the industry have driven a decline in helicopter use by explorers. But is the scrapping of helicopter support during remote mapping campaigns actually a financial blunder?

Junior mining exploration companies may be surprised by how cost-effective helicopter support can be for geological mapping. Nathan Shute Photo

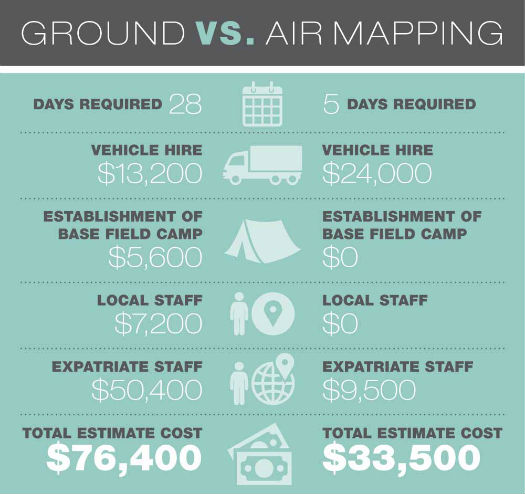

Recently, while contracting to a junior exploration company new to Zambia, our geological team used a Robinson R44 for a rapid grab sampling campaign; it proved to be highly economical and time-effective. The company had no assets and no personnel in the country; a typical situation for a junior exploration outfit entering a new jurisdiction. All technical equipment, safety kit and camping gear would have to be purchased or hired, and our initial plan was to conduct ground mapping over a period of 28 days, which was priced accordingly:

• Vehicle Hire

Companies cannot commit to the capital expend-iture of purchase for the first reconnaissance mission. In some jurisdictions, it is also necessary to hire drivers. Fuel must be purchased and the local supply may be unreliable. Furthermore, safety and evacuation procedures should mandate a minimum of two vehicles, driven in convoy, when accessing remote sites. Zambian car hire is expensive, and our original budget allocated US$400 per day for two 4×4. Our overall estimated cost for this was US$11,200, plus a fuel allocation of US$2,000.

• The Establishment of a Base Field Camp

This would include the cost of tented accommodation, mess, first aid and health, safety and communications equipment. The cost for a very basic setup would be US$5,600.

• Local Staff

Field hands, a camp manager, cook and a night watchman are all necessary. All these people must be housed and fed, at a cost of about US$7,200.

• Expatriate Staff

Junior explorers contract expatriate staff for short exploration campaigns, as they do not have the funds to keep full-time staff on the books until a project is proven and funded. An explorer will pay upwards of US$1,000 per day for an exploration manager and around US$800 per day for the exploration geologist. The cost for this campaign would reach US$50,400. With such high costs for these “skilled” staff, time-saving and money-saving are one and the same.

Most reconnaissance mapping will involve grab sampling of rocks that each weigh between 500 grams (1.1 pounds) to 1 kilogram (2.2 pounds). Amanda Geard Photos

The total cost of US$76,400 was just under the budget supplied by the company, and therefore left little room for the inevitable surprises that accompany remote field work. Furthermore, no roads crossed the 2,000 square kilometers (770 square miles) of tenure, and sample sites were spread across the entire area — the closest boundary of which was already 40 kilometers (25 miles) from the nearest navigable track for a vehicle. The company’s safety policy dictated that we should not be further than 12 hours’ walk/drive from an evacuation point, and so we needed to provision for helicopter extraction in the case of emergency. The whole operation was becoming bigger than Ben Hur, particularly for first-pass mapping of an underexplored region.

Our first round of calls to query emergency helicopter support turfed up Ed Farmer, owner of Sky Trails in Zambia, who normally runs air safaris. We were keen to get Farmer on board for emergency standby, with his R44 able to complete the roundtrip from Lusaka to our proposed pick-up point in 120 minutes.

Sky Trails has the only R44 in Zambia. “We imported this particular machine to gain a foothold in a new market for Zambian aviation, and open up possibilities for a wide spectrum of work previously either not possible or much more time consuming and expensive,” said Farmer. “The R44 is a very affordable machine to operate but capable of a wide range of work in remote locations, so it ideal as a first step.”

And affordable it was. At a quote of US$800 per hour we started to crunch some numbers. We estimated that we would need five days of flying to cover the ground, with six hours of air time each day, to include the 120-minute return commute from Lusaka airport. This brought us to a budget of US$24,000, plus a drastically decreased expatriate bill of US$7,500, with a buffer of US$2,000 for accommodation, subsistence and equipment for the week in Lusaka.

We weighed up the economic and time implications of the 28-day foot-supported program, at a projected cost of US$76,400, and compared it to our quick-fire helicopter supported sampling campaign at a total of US$33,500. These figures were all we needed to convince the board, and so we flew in, completed first pass exploration and submitted our samples within one week. Funding followed promptly, and now we are on our way to a full field program.

Junior explorers think hard about money, purse strings are tight and the financial risk is high — but with high staffing costs and short field seasons in many countries it can be easy to fall into the trap of forgetting that time is money. I would encourage helicopter charter companies to seek out junior explorers in their jurisdiction (your local Geological Survey will be able to assist), and encourage them to think on a “cost per sample” basis rather than the traditional “cost per day” mentality.

“Every time we do any job for the mining industry, everyone says how it exceeds expectations for productivity,” said Farmer. “Hopefully work will keep spreading and business will pick up with time.”

What is expected of the pilot?

Be prepared to let the rocks dictate the program. During early stage mapping the first assessment of an area involves sampling rock outcrops (cliffs or large areas of rock) or subcrops (boulder fields or lone rocks).

You may be asked to transport the geological team to a specified location, but often a whole region may need to be sampled. In the latter case, the quality of satellite imagery may not have been sufficient to locate specific sampling points, and therefore the first day may be a matter of gridding an area and marking on anything that looks like a rock and a possible nearby landing site to be sampled in the following days.

Clear presentation of the pricing structure for the helicopter is critical — with any agreements relating to minimum flying hours and standby (while sampling, for example) clearly explained and agreed beforehand.

The Sky Trails Robinson R44 prepares to leave a drop point during mapping in Zambia. Amanda Geard Photo

Amanda Geard is an exploration geologist and project generator who has worked across Australia, South America, southeast Asia and Africa. She currently runs a consultancy with her business partner which specializes in targeting and acquiring unexplored ground for junior explorers looking to break into new markets in Africa.

Hi

I need the email Amanda Geard

I have projects to offer

Thank you