Since it was first established in 1929, the primary mission of the California Highway Patrol (CHP) has been enforcing traffic laws and promoting vehicle safety across the state’s extensive system of highways and byways.

In the 1960s, the CHP adopted the use of aircraft, a mix of airplanes and helicopters, which provided effective alternatives for traffic control and law enforcement. The CHP’s Office of Air Operations (OAO) was created to manage and coordinate the program throughout agency’s eight operational divisions.

The first helicopters were Hughes 500s and Fairchild Hiller FH-1100s. In the 1970s and ’80s, the CHP acquired additional rotary-wing aircraft: Bell 206 LongRangers, MBB Bo.105s, and a Eurocopter (now Airbus Helicopters) AS350 BA AStar. The improved performance of these helicopters allowed the CHP to expand its mission capabilities to include medevac and search-and-rescue (SAR) using short-haul and hoisting techniques. These new capabilities were quickly recognized as crucial lifelines, especially for those in rural communities and remote areas of the state.

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the CHP moved to standardize its helicopter fleet. It began taking delivery of what would ultimately be 15 AS350 B3 AStars, each equipped with rescue hoists and the latest in infrared and imaging technology.

The B3’s enhanced high and hot performance was a game changer for CHP’s SAR mission and it became a highly regarded workhorse. It excelled in the scorching desert environments supported by CHP’s Southern Division and in the Inland Division’s high-altitude work in the mighty Sierra Nevada mountain range, home to 14,505-foot (4,420-meter) Mount Whitney, the highest point in the contiguous United States.

In 2015, with several of the agency’s B3s eclipsing 16 years of service, a multi-year fleet replacement plan with Airbus Helicopters delivered the first of what will ultimately be 15 H125s, an upgraded and more powerful variant of the popular AS350 AStar (see p.40, Vertical 911, Summer 2016).

“The H125 offers an increase in power, increased gross weight, advanced avionics, upgraded FLIR, more capable hoist, and a full suite of law enforcement radios to meet all our communication needs throughout California,” said CHP chief helicopter pilot Sergeant Tyler Johns. “It has increased our ability to do our mission in the high, hot, and heavy scenarios we are routinely faced with in the rescue environment. The increased power means we can have more fuel, more personnel, more equipment, or increased performance margins while conducting high-altitude rescues.”

One important performance item Johns highlighted is the time the H125 can sustain maximum takeoff power. He said, “The maximum permissible power that can be used for takeoff (MTOP) for a limited time in the H125 is 30 minutes. The MTOP for the B3 was five minutes. A lot of our hoist extractions occur at very high altitudes, 10,000 to 14,000 feet, and require using MTOP to complete the hoist operation. Having more time allowed in that power range increases our safety in the operation without the undue pressure of rapidly executing a very complex rescue operation.”

With CHP’s eight operational divisions spread all throughout the state, the various helicopter units are somewhat isolated from each other and rarely have an opportunity to interact or train together. As a result, many aspects of SAR techniques and crew communications were not necessarily standardized across the organization.

In hoist operations, for example, most crews favored a technique referred to as “static hoisting” as the basis for their missions. As O’Brien described it, “Static hoisting is bringing the helicopter into a hover over the site, then deploying the hoist hook to the ground. Then recover the hook before beginning any forward movement, departing the scene.”

However, the individual crews had the freedom to develop their own procedures and methods for communicating. CHP pilot and OAO helicopter maintenance officer Bryan Souza said, “We all operated about the same but perhaps the divisions spoke a different language, like we were not entirely on the same sheet of music.”

An outside perspective

About the time the H125s were coming on line, OAO began an assessment of existing policies relating to SAR operations. It was noted that while the organization had enjoyed many years of success and a remarkable safety record, it had never invited an independent audit from an outside provider to examine how it was doing business, especially with respect to hoist and external load operations.

OAO officials understood that, given the program’s years of success, the suggestion of an outside audit and training provider might be met with skepticism if not outright push-back. But they also understood the potential risks they would assume should they not pursue seeking a fresh perspective.

So after careful considerations of several independent SAR consultants and training providers, CHP chose Oregon-based Air Rescue Systems (ARS). According to CHP OAO chief flight officer Larry O’Brien, “In my search for a company to provide this training it was essential that whoever we bring on board understand our mission. After talking with several providers I felt most comfortable with Bob [Cockell] from ARS. I felt he really understood where we were and where we wanted to go with the program.”

A three-year program was developed, with ARS providing on-site training in seven-day blocks for small groups of senior training pilots and flight officers as a “train the trainer” model.

O’Brien recalled, “This was a big leap for us! We had some real strong personalities, ‘Doubting Thomases’ at the beginning, who were skeptical. We really had not had an outside agency look at our program and now we’re having somebody take a look at what we do and we’re opening a window to outsiders to see what’s going on. Quite frankly it made us feel a little vulnerable.”

ARS vice president Cockell and his trainers were keenly aware of the potentially sensitive nature of the situation. The CHP crews were seasoned SAR professionals with years of successful missions to their credit, often in extreme environments. ARS on the other hand was an unknown outsider to the CHP, and earning the crews’ acceptance wasn’t at all guaranteed.

Cockell said, “Look at their long history, they’ve been doing this for many years. So we knew [they] were going to have a lot of strengths going into the process. Just the experience, flight time, and their working environment is so varied, so I knew there would be a great capability that would surface. With this in mind, I toned the training toward that, to use what they have been doing and not just discard or disregard all their collective past knowledge. We needed to honor the proficiency and the legacy of the program they created.”

The ARS course utilizes a “crawl, walk, run” approach to teach indirect vertical reference (IVR), a method for precision hoisting that emphasizes dynamic, fluid aircraft movements and precision load control techniques.

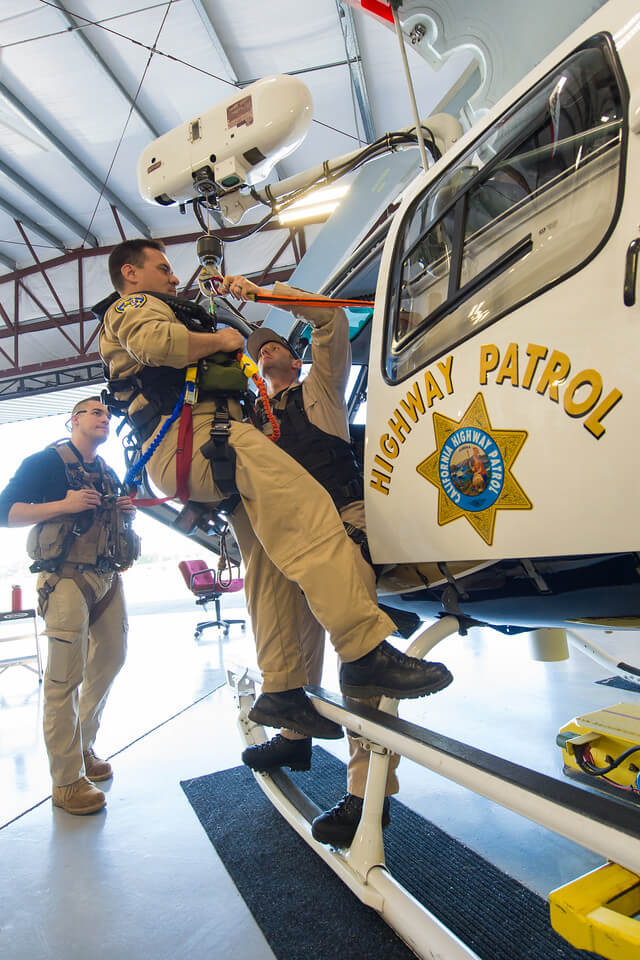

Courses begin with two days of classroom instruction covering operations safety, risk management, crew resource management (CRM), “rotor-flow dynamics,” and the physical laws and constraints relating to hoisting and load control. An afternoon is then dedicated to aircraft rigging and equipment familiarization to include ARS’ innovative AStar Human Anchor Plate (HAP) and the new Goodrich hoists installed on the H125s.

The AStar HAP was designed by ARS along with the Utah Highway Patrol to provide much-needed additional anchor points inside the rear cabin of AStars configured with LifePort’s rear seat mounting rails. Meanwhile, the Goodrich hoist has performance enhancements over the CHP’s previous model and enhances mission capabilities. It has an increased load capacity allowing “two up” attended hoist rescues. Additionally, in the dynamic hoisting environment, the increased speed of the hoist aids in load control and ability for precision hook placement. It also means less time in an out-of-ground-effect (OGE) hover during the actual hoist operation.

The balance of the course instruction is conducted in the field. Each student is given the opportunity to perform literally dozens of hoist evolutions each day in progressively challenging real-world environments.

Tone, tempo, and timing

At the core of the IVR method is the communication that must exist between the flight officer/hoist operator and the pilot, and the ability to accurately express one’s needs, directions and information.

Most traditional hoisting techniques utilize rigid commands to direct single-path or “one-ended” movements of the aircraft. Flight officer Matt Calcutt said, “In our old way of communicating we would open and close a command before issuing another. For example, if the aircraft needed to go ‘forward and left’ the command would be given, ‘forward’ to a particular point and then a second command of ‘left.’ So the pilot would follow that ‘forward’ command: 5… 4… 3… 2… 1… stop. Then be given the ‘left’ command: 5… 4… 3… 2…1… stop. This creates a right angle.”

The ARS method promotes “compound movements” like forward and left or down and right. Voice inflections are used to convey to the pilot such things rate of closure. Calcutt explained, “A command delivered such as ‘easy left’ lets the pilot know he has more ground to cover than if the flight officer uses an inflection to say, ‘eeaassy left’ which would convey a shorter, more precision movement of the aircraft. The whole goal is to have that pilot fly that aircraft as long as they can and then pass the control of the aircraft to the hoist operator who gives clear verbal commands to the pilot to precisely position the aircraft.”

“What we teach is a casual conversation that’s very fluid, based on the 3 Ts — tone, tempo, and timing — in our message,” said Cockell. “We use coordinated, compound progressive movements. So the aircraft is always moving efficiently. You’re either descending and moving right, maybe back, up and left… That’s the way you fly the aircraft, so why not hoist that way? It reduces the time you’re sitting there and it definitely reduces the amount of unwanted movement the load receives due to aircraft stair-stepping movements.”

Another critical element of the ARS method is cable hand input and thumb control of the hoist control’s pendant controlling the cable speed. This provides fine control of the load required for precision placements.

Calcutt said, “While the thumb control exercises may be viewed as baby steps in the beginning, they’re foundational in teaching a hoist operator the skills of finessing the hook, especially within close proximity to the ground, allowing the load to be placed very gently and with great precision.”

Compared to its old method of static hoisting, CHP has now embraced a dynamic hoisting technique. As O’Brien explained, “Our new technique of dynamic hoisting is deploying the hook prior to arrival and then having it arrive in hand as the helicopter holds overhead briefly. As soon as the load is off the ground and clear of obstacles, we transition to an easy forward and then once recovered to the aircraft, [are] cleared for forward flight.” O’Brien said the technique is faster and limits the amount of time the helicopter spends in a hover and in the “avoid” area of its height-velocity curve.

Presently, the CHP is operating a fleet of 15 helicopters including eight H125s. Of those, 12 are fully SAR capable. The other three aircraft operate out of the Metro Division in the Los Angeles Basin and are primarily used for law enforcement support. Two additional H125s are expected to join the fleet in the next two years. Budgets will dictate the timing of the remaining purchases to completely turn over the fleet.

In 2017, the 12 CHP SAR aircraft flew nearly 10,000 hours, conducting 471 SAR missions throughout the state. They conducted 351 Advanced Life Support (ALS) medical transports and performed 153 hoist rescues.

With the agency having recently completed its fourth course with ARS, the overwhelming response from CHP pilots and flight officers is clearly energized enthusiasm. O’Brien said, “The ARS training really opened our eyes and gave us a real understanding as to the dynamics involved in hoisting and learning thumb control of the cable. In the past if we developed an oscillation we’d just bring the load up to the helicopter real quick and get out of there. But now, understanding the dynamics of everything, we can now control the load and fix oscillations and bring a controlled load up to the helicopter.”

Souza said, “With the ARS training, we now know what we didn’t know. It wasn’t that we were doing anything wrong. But now we’ve just learned better ways of doing it. And by doing this it has increased our efficiency and has helped minimize some of the risks. And the ARS training will help us standardize the training program for hoist operations throughout the entire agency.”