Rudolph (Rudy) John Enstrom was born in Crystal Falls, Michigan, on June 23, 1916. He was the son of Erick and Hilda Enstrom, the owners of a local sawmill and lumber business. After graduating from high school in 1934, Rudy worked for a while in his dad’s sawmill, which is where he developed his basic mechanical skills. He then attended the Hemphill Engineering School in Detroit, Michigan.

Around 1940, Rudy was hired by the North Range Mining Company as a surface foreman and master mechanic at the Warner iron mine at Amasa, Michigan. It was while he was working there that he became fascinated by helicopters. He was soon finding out all he could about rotary-wing aircraft and closely followed the progress of Sikorsky Aircraft with its experimental VS-300 and R-4 helicopters, and Bell Aircraft Corporation’s Model 30.

Despite having no background in aviation, Rudy spent all his free time figuring out how he could manufacture a flying helicopter while still holding down his job at the iron mine. His first tinkering and sketches took place in a garage next to his home, and later at his father’s sawmill.

By 1943, Rudy’s first attempt at a design was ready for initial tests. It was a coaxial aircraft, powered by a 50-horsepower Continental engine. However, he immediately saw that there was a lot of vibration, and abandoned the design.

After much consideration, he switched to a helicopter with a single set of rotor blades and a conventional tail rotor. Over time, he was able get some air under the tires, but only just.

Rudy’s third helicopter did take off, but he lost control of it and crashed. The fourth design was built on wheels with a canted tail, like the Sikorsky R-6. It didn’t fly any better, and barely hovered. The fifth — also on wheels, with a single main rotor and tail rotor — was beginning to look more like a functioning helicopter. Rudy was proud of how far he had come — all without professional engineering help. The aircraft hovered, but he lost control once again, and the main rotor blades hit the ground. He was devastated, but unhurt.

At this point, Rudy considered giving up. But the damage to the machine was not severe, and he decided to make the necessary repairs and switch from wheels to landing skids.

The mine closed in 1958, but Rudy’s wife insisted that he stay in the area and complete his helicopter project rather than move for another mining job. And, by the end of the year, the helicopter was ready again.

Rudy labelled this sixth design the F-27. It had a main rotor diameter of 30 feet (nine meters), was 36 feet (11 meters) long, seven feet (2.1 meters) high, weighed 1,200 pounds (545 kilograms) including the pilot, and was powered by a 115-horsepower engine. It was completely hand-built, except for the engine.

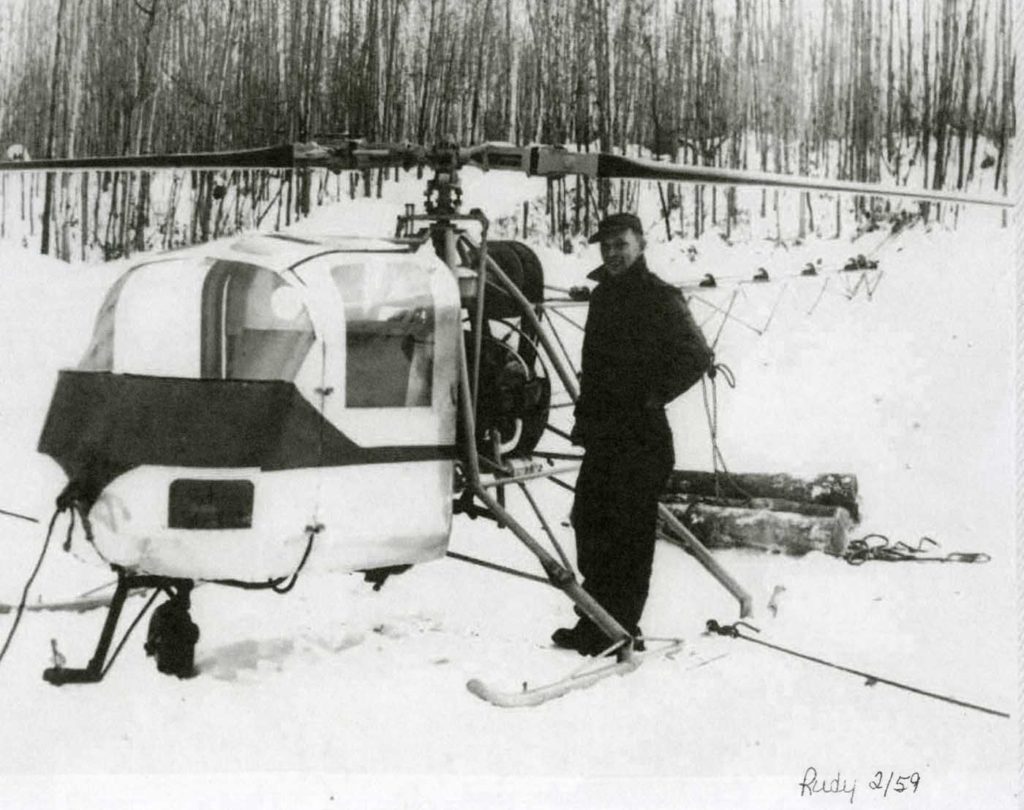

In January 1959, he successfully hovered the aircraft about six feet (1.8 meters) above the ground while tethered, and kept it under control. Rudy was ecstatic. Having devoted 15 years to his helicopter endeavor, he had achieved his long-held ambition.

“His dream was realized in February 1959 when Rudy flew his helicopter,” Rudy’s wife, Edith, wrote in a letter. “Rudy had had no helicopter flying instruction, so he had to teach himself to fly — which was another challenge.”

Taking Flight

News of the successful flight quickly attracted interest, resulting in Rudy performing demonstrations for two groups of businessmen (including Jack M. Christensen), as well as two representatives from the Parsons Corporation (which built rotor blades for several helicopter manufacturers).

The businessmen were interested in manufacturing the helicopter, while the representatives from Parsons (engineer-technician Frank Bolaro, and contract manager and test pilot Fred Hill) were impressed with the aircraft’s design features and operation. The main rotor control irreversible mechanism was unique, with its features providing adjustable control sensitivity. The Parsons duo recommended that the helicopter’s landing skids be modified so that they provided energy absorption during rough landings, but their favorable report increased interest in Rudy’s helicopter.

In March 1959, Rudy approached mid-west helicopter pilot pioneer Albert H. Luke at the Lewis College of Science and Technology in Lockport, Illinois. Rudy asked about getting a helicopter pilot’s rating, and noted his 20 hours of solo time in conventional aircraft. “I have about three hours of solo time,” said Rudy of his experience in his experimental home-built helicopter. In a follow-up letter, he told Luke that a corporation was being formed to manufacture a helicopter of his own design.

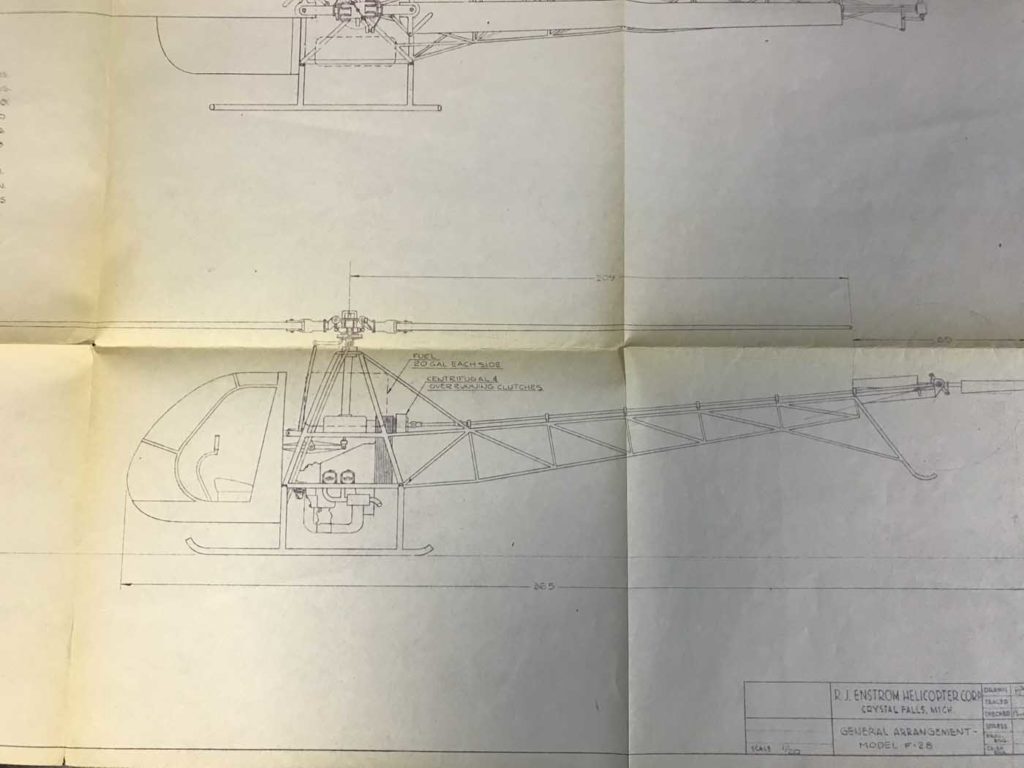

The R.J. Enstrom Corporation was formed in Crystal Falls in April 1959. By September that year, the three-view drawings of the new Enstrom F-28 had been completed, and the initial construction of the experimental F-28 was soon underway in Rudy’s garage. Luke met Rudy that same month and saw his experimental helicopter for the first time.

By 1943, Rudy’s first attempt at a design was ready for initial tests. It was a coaxial aircraft, powered by a 50-horsepower Continental engine. However, he immediately saw that there was a lot of vibration, and abandoned the design.

After discussions with Rudy, Luke connected with Christensen to offer his technical expertise and consulting.

Following the first stockholders meeting of the R.J. Enstrom Helicopter Corporation later that year, Christensen was elected president, with Rudy named VP and general manager. Other board members included Albert (Alb) Ballauer (an aeronautical helicopter design engineer from Parsons), Luke, and businessmen Edgar E. Erdmann and Douglas E. Jones, both from Menominee, Michigan.

At a board meeting in December 1959, the company established sales and manufacturing teams, and as the year ended, everything was going very well for the little helicopter company.

Ballauer was given the task of running the certification program, while Luke and Fred Hill were selected as the first pilots to fly the F-28.

On Jan. 12, 1960, the preliminary basic data for the Enstrom pre-production prototype was released. It was a two-seat helicopter with a single two-bladed main rotor and conventional tail rotor. The main rotor had a diameter of 34 feet, 10 inches (10.6 meters). The helicopter was powered by a 180-horsepower Lycoming O-360 engine. It had two 40-US gallon (150-liter) gravity feed fuel tanks installed. The drive system was a belt drive, with a single stage bevel gear speed reduction torque tube to the tail rotor.

The aircraft’s gross weight was 1,700 lb. (770 kg), and it had an empty weight of 1,005 lb. (455 kg). Its useful load was 695 lb. (315 kg), and it had a maximum speed (at sea level) of 100 mph (160 km/h).

The company expected to sell the helicopter for $20,000.

Moving Home

In August 1960, the R. J. Enstrom Corp. — still a small company, with just 13 employees — moved from Crystal Falls to the Menominee County Airport in a hangar/shop owned by the city.

The pre-production experimental prototype F-28, registered as N915D, was completed on Oct. 17, 1960. It looked close to its original design drawings, except for the cabin enclosure and the tail skid. Tie-down run ups began immediately.

On Nov. 12, 1960, Luke became the first pilot to fly the F-28, bringing it into a hover at the Menominee airport. Over that weekend, Luke and Hill took several turns flying the aircraft, mostly conducting hovering tests. The two immediately noted strong vibration issues with the helicopter. Ballauer believed this would be a relatively simple fix — a matter of replacing or reworking some of the parts that were giving them trouble. These changes were made after the flights.

However, the solution didn’t prove to be quite as straightforward as hoped, and Ballauer eventually began developing a new three-blade rotor system to fix the issue. This was installed in February 1961. Luke took the F-28 for a five-minute flight, and was impressed with the smoothness. The vibration problems seemed to have been solved.

The following month, test pilot James (Jim) Terrell joined the program, and made his first familiarization flight in the F-28. He told Christensen it was “the smoothest running helicopter he had ever flown.”

The initial test flight program was complete, and the team turned its attention to building two experimental three-place prototype pre-production F-28s. The first flew in May 1962, and even took a break from its program duties to go on display at the Helicopter Association of America Convention in Dallas, Texas, that year.

Tragedy struck the program on Nov. 13, 1962, when the first pre-production F-28 crashed, killing test pilot Jim Terrell. He had just taken off from the Menominee airport and had reached about 300 feet (90 meters) when he experienced trouble flying the aircraft. The official accident investigation found nothing to indicate a mechanical malfunction or failure. The Enstrom company vowed to complete the type’s certification program.

Hill, now vice president in charge of sales, said the F-28 was about two-thirds of the way through tests for certification by this point, with the company having invested about $600,000. Enstrom felt it had sufficient funds to get through certification and into production by mid-1963.

The second pre-production F-28 was completed in May 1963. Flight testing started right away, with Mott Stanchfield hired as the company’s new test pilot.

In November 1963, the company moved into a new $70,000 building at the Menominee County Airport, which had been purpose-built for it by the Menominee Industrial Corporation. The building was purchased on a 10-year rental-purchase contract.

Work continued into 1964 on the certification of the F-28, as money grew tight for the company. To expedite certification, it temporarily shelved the rigid rotor system in favor of a fully articulated rotor. It planned to fully explore the merits of the rigid rotor once the F-28 was in production.

During final tests, the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) test pilots flew the F-28 for close to 50 hours. The aircraft’s stability, lack of vibration, low noise level, and high speed appeared superior to other helicopters being produced at the time.

Ballauer said he believed projected operating costs were half that of the closest three-place competitor, with additional advantages in appearance, flying qualities and advanced design.

Getting into production

In February 1964, Lewis College put deposits down for two new F-28 helicopters, to be used for student training and powerline patrols. These would be the first Enstrom helicopters to be delivered, scheduled for that summer.

However, finances at the company continued to be tight. By October, operations were reduced, as Enstrom found it impossible to pay any bills except those which involved payroll or materials needed for certification. It was only doing development and test work as required for certification. All production was deferred. The company planned to complete and submit all data to the FAA by the middle of December. New financing would be required to get production of the F-28 underway.

Rudy resigned that October due to the company’s financial difficulties and setbacks. It was not an easy decision for him. He joined Lakeshore Incorp., designing and developing heavy equipment for use in iron mines. L.E. Jones took over as the company’s new general manager.

After more than four years of work, Enstrom finally received the coveted type certification for Rudy’s dream of a practical helicopter on April 15, 1965. At this point, Enstrom had 30 firm orders for F-28s.

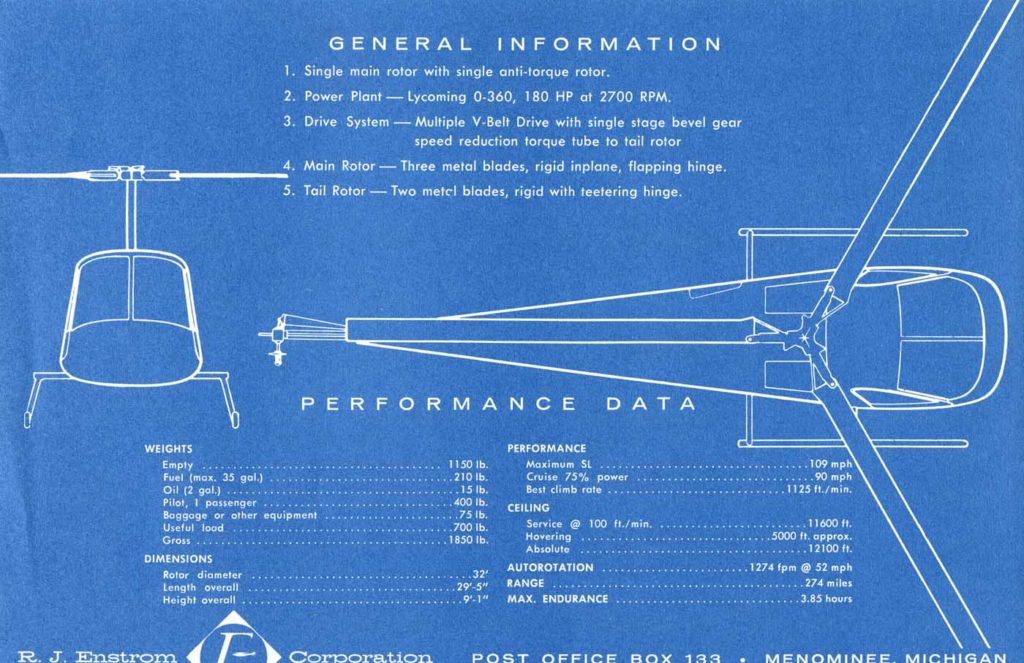

The F-28 was certified with a three-bladed metal rotor, at an empty weight of 1,150 lb. (520 kg) and a gross weight of 1,850 lb. (840 kg). The rotor diameter was 42 feet (12 meters), it had a length of 29 feet, five inches (nine meters), and a height of nine feet, one inch (2.7 meters). Its maximum speed at sea level was 109 mph (175 km/h), with a cruise speed of 90 mph (145 km/h). Its operating ceiling was 11,600 feet (3,525 meters), and it had a range of 274 miles (440 kilometers), with an endurance of 3.85 hours.

Unique to the F-28 was the lack of the exposed pitch change links for the main rotor. These were contained inside the main rotor shaft, helping to lower aerodynamic drag.

The price for a new F-28 was listed as $27,400, and Enstrom began demonstrating the aircraft to potential new customers.

However, deliveries didn’t begin until 1966, with the first F-28 handed over to the WCUE radio station in Akron, Ohio on Feb. 12, 1966 (Lewis College had cancelled its agreement to receive the first of the type the previous year).

Another five F-28 helicopters were delivered in 1967, and 12 in 1968. The more powerful F-28A also came out in 1968.

By May 1971, Enstrom had delivered 50 F-28s. Despite a slow start, the type had found its niche in the helicopter market, and sales were rapidly increasing.

While Rudy took some time away from the industry to start his own heating business, he eventually went back to his first love – helicopters — and was employed by Hillman Helicopters as its chief engineer in Scottsdale, Arizona. Rudy retired in 1983 to spend more time with his family. He died on Sept. 25, 2007, in Iron River, Michigan.

“My father had an unexplainable passion for airplanes and helicopters from an early age,” said Rudy’s daughter, Connie Enstrom-Sandri. “Through the years, his passion never waned. I admired his patience, perseverance, and unending enthusiasm. He proved that dreams could come true. To see his vision fulfilled was an exciting time in our lives.”

In 2019, the Enstrom Helicopter Corporation (as it is now known) celebrated its 60th anniversary. It has produced over 1,300 helicopters, which operate in over 50 countries around the world — and it is still manufacturing F-28s (now upgraded to the F-28F version), along with the 280FX and turbine 480B.

Today, Enstrom is a wholly-owned subsidiary of a Chinese company, Chongqing General Aviation Group Co., Ltd. (CGAG), but it is still located in the same location in Menominee.

The author would like to thank Jahn A. Luke (son of Albert Luke), Kenneth Swartz, and Jackie Kamps/Enstrom for contributing to this story.

I grew up about 50 miles from the Enstrom factory and remember (?) a story in the Peshtigo times that was about Rudy having to knock out cinder blocks from his basement to get one of his early helicopters out – it used black iron pipe for the skids. I don’t know if it’s true, but a good story. (BTW, I fly Enstroms – nice machine)