The brightly painted red, white, and blue Black Hawk helicopter approaching the Yuma International Airport in Arizona that autumn afternoon wasn’t anything out of the ordinary. It’s likely that nobody raised an eyebrow when it touched down on a remote portion of the airfield and taxied to an isolated hangar on the far side of the runways, or took much notice of the group of individuals watching intently as a tug connected a tow bar and pushed it inside.

When it emerged the next day, however, people were undoubtedly paying attention. The civil Sikorsky S-70 that was pushed into the hangar had been transformed overnight into a menacing armed medium attack helicopter. An imposing array of military weapons had been mounted beneath two small “wings,” and an electro-optical/infrared (EO/IR) sensor and laser designator had been installed on the nose.

Was this a prop for a Hollywood movie? No, this was the real deal, and it was about to embark on a mission to demonstrate its lethal capabilities.

Building on a Legacy

The Black Hawk has a distinguished legacy. Introduced in 1972 as Sikorsky’s Model S-70 (YUH-60), it was chosen as a prototype finalist for the Utility Tactical Transport Aircraft System (UTTAS) development program, competing against the Boeing-Vertol Model 179 (YUH-61).

UTTAS was a U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) competitive evaluation seeking a new utility/assault helicopter for the U.S. Army to replace the aging Bell UH-1 Huey for air assault, air cavalry, and medical evacuation missions.

By December 1976, the Army had completed the competitive development phase and awarded the contract to Sikorsky. Once delivered to the Army in 1978, the S-70 became known by its Mission Design Series (MDS) designation as the UH-60A. The DoD named it “Black Hawk” after the Sauk American Indian leader and warrior.

Subsequent variants of the Black Hawk provided improved performance, making it highly adaptable to an expanded variety of missions. Today, the DoD has 33 MDS variants of the H-60. They serve throughout all branches of the U.S Armed Forces and with 29 foreign military operators.

The capabilities of the H-60 are also highly regarded by civil operators in the form of the legacy S-70, which has been adapted for aerial firefighting and construction by operators including Firehawk Helicopters of Boise, Idaho. Sikorsky continues to manufacture an international military variant of the Black Hawk, the S-70i, which is used by many foreign governments for military applications and VIP transportation.

The U.S Army’s 160th Special Operations Aviation Regiment (160th SOAR) was the first operator to adapt the Black Hawk as an armed medium attack helicopter. The MH-60A DAP (Direct Action Penetrator), first fielded in 1989, was configured to carry weapons and used as an armed escort and for close air support missions.

Today’s modern variant, the MH-60M DAP, is the only such armed Black Hawk presently serving U.S. military operators. Its weapons include pintle-mounted 7.62mm Miniguns, both crew-served and fixed forward-firing; bore-sighted Orbital ATK 30mm chain guns on fixed mounts; and 70mm rockets. Precision weapons like the Hellfire air-to-surface or Stinger air-to-air missiles are options when integrated with the DAP EO/IR sensor and laser target designator package.

In 2012, the U.S. Army was facing tough decisions regarding its first generation Black Hawks, many exceeding 30 years of service. For these helicopters to remain operationally viable, they would require extensive and expensive inspection, overhaul, and modernization.

To ensure operational readiness, the Army’s Utility Helicopter Program Management Office created the Black Hawk Exchange and Sales Team (BEST) program. Over a period of 10 years, the program will divest 600 to 800 legacy Black Hawks consisting of mostly A and L models.

In its basic concept, the BEST program works as follows: as new UH-60M models roll off the Sikorsky assembly line destined for the U.S. Army, an “obsolete and non-excess” utility Black Hawk is pulled from the Army inventory and demilitarized. These older aircraft then enter a process making them available via sale or exchange, first to federal and state government agencies, and then to Sikorsky. Those aircraft not selected by Sikorsky will be transferred to the Federal General Services Administration to be auctioned off to U.S. and international contractors.

New Opportunities

The anticipated influx of these UH-60As to the resale market inspired a number of companies to assess how the aircraft might be utilized in their next life. Many believe that, after refurbishment, foreign governments will be interested in purchasing these aircraft to fulfill any number of mission roles.

One such company was Butler National Corporation, a relatively small aerospace firm producing, among other products, weight- and space-saving gun control units (GCUs) for the Orbital ATK line of automatic cannons and chain guns. In 2012, Butler was coming off two important projects. One involved development of a lightweight gun control. The other was an innovative special mission portable weapon system, integrating the M230 30mm chain gun aboard a U.S. Navy MH-60 Seahawk. In considering these projects and the divesture of Army Black Hawks, Butler’s engineers recognized an opportunity.

“With the Seahawk program, we developed a carry-on/carry-off weapon system — a portable unit containing all the power and signal distribution in one portable flight box and GCU, cables and harness in a separate carrying case, that could be quickly and easily installed into an aircraft,” said Brian Reilly, Butler’s VP of engineering. “From this we saw the potential to develop a gun control system that could convert existing utility S-70 and UH-60s into gunships and in a very short period of time.”

In early 2015, Butler National teamed with four other companies, each with similar customer interests. They were Fulcrum Concepts, manufacturer of the ARES weapon management system; weapon manufacturer Orbital ATK; aerospace composite specialist AGC AeroComposites, and defense contractor Raytheon. Together they formed the UH-60 Weaponization Alliance.

The next step was identifying the other companies with the products and expertise to fully develop the complete weapons package, which the Alliance branded as the Modular Weapons System (MWS).

In January 2016, L-3 WESCAM began development of its own portable weapon system for the Black Hawk. This was a scaled-down version of its Mission Adaptable Weapons System (MAWS), which at its core features Fulcrum’s ARES weapon management system. Two larger MAWS packages for military fixed-wing aircraft, including the AC-208 Combat Caravan and the heavily armed AC-130 Hercules, have been in use for two years. Similar to the Alliance concept, L-3’s venture was intended to be a cost-effective way to rapidly reconfigure a utility Black Hawk into an armed aircraft in six hours.

Paul Jennison, VP of government sales and business development for L-3, said, “Most of our current and proposed international customer base cannot afford dedicated armed or gunship assets like the United States, and arming an aircraft presents significant cost, schedule, and technical risks. WESCAM’s solution is to offer an integrated Mission Equipment Package that allows the customer dual-use utility/cargo range-proven mission and armed recon/attack mission combined with reduced cost schedule and technical risk.”

By the middle of last year, WESCAM’s product was in the early stages of development, but was fully funded and prepared to move forward. However, the company still needed support from other vendors. The Alliance, on the other hand, had already assembled all of its vendors and had over a year’s head start in developing its MWS. In the interest of maximizing efficiency and utilizing each other’s strengths, WESCAM and the Alliance developed a strategy that benefited both parties.

WESCAM would sponsor an integration test flight and qualification for the newly developed portable weapon system and provide resources for key elements of the test program. This included the range contract with the Army’s Yuma Proving Grounds (YPG) and the lease of a civil S-70 helicopter from Firehawk Helicopters as the test platform. (As a longtime S-70 operator, Firehawk had also been part of the joint venture that secured the first restricted-category type certificate for the UH-60A from the Federal Aviation Administration.)

WESCAM would benefit from the sharing of resources supplied by the Alliance. In return, Alliance members would accomplish all of their goals at greatly reduced costs to them and retain ownership of their work on the MWS. They would also be provided with valuable test data gathered by WESCAM. In all, there were more than a dozen participants in the qualification event.

This past October, when the Firehawk S-70 rolled out from the Yuma hangar, it marked the culmination of nearly two years of work on the part of the Alliance and its recent partnership with WESCAM.

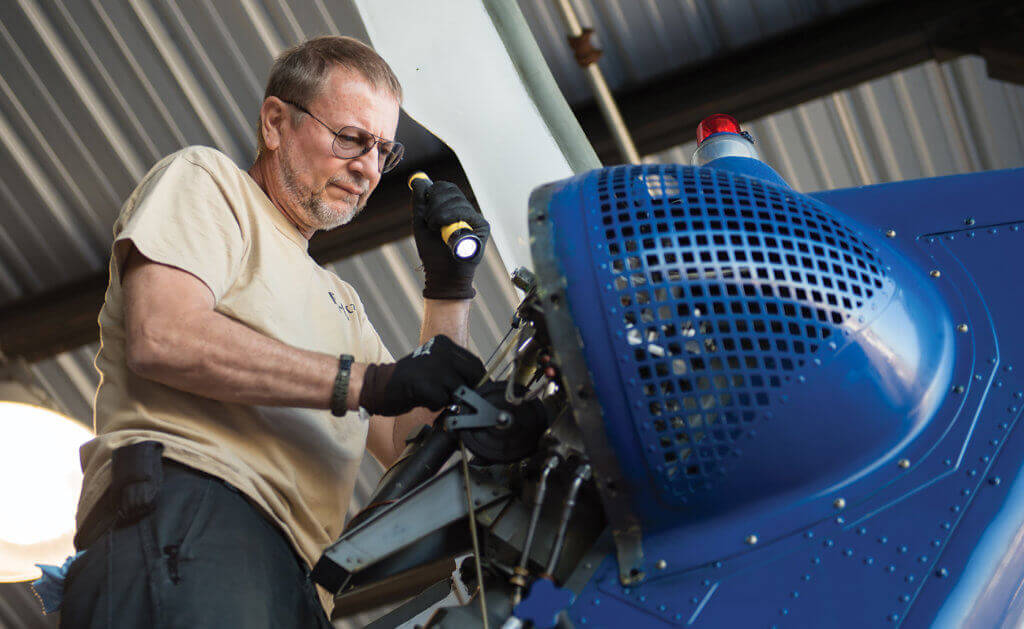

A team of technicians and engineers needed just six hours to transform the S-70 from utility workhorse to medium attack helicopter. The process involved installation of an MX10 EO/IR sensor, aiming laser, two Lightweight Armament Support Structure (LASS) external “wings” manufactured by Unitech Composites, Inc. (formerly ACG AeroComposites) and a weapon control station in the rear cabin. The subsequent installation and change out of each weapon system went relatively quickly.

After the installations, a series of systems and weapons checks on the ground ensured the aircraft was ready for the next step — the all-important flight test qualifications at the nearby YPG.

Putting it all Together

During the flight tests, one of the two pilots aboard the S-70 used a helmet outfitted with the Thales Visionix Scorpion, touted as the world’s only full-color (24-bit) helmet mounted cueing system. This provided the pilot with a virtual 360-degree heads-up display overlaid onto the rest of his “real-world” environment.

John Daley, Thales director of business development, explained, “Scorpion was integrated into the L-3 WESCAM system to provide video and bore-sight aiming information direct to pilots for continuous eyes-out, on-target sighting over a wide field of regard. This lets the pilot see anything in the sensor’s field of regard, just by turning his head in that direction.”

Over the next two days, the armed S-70 demonstrated successful target lock-on firing of 2.75 inch APKWS rockets, the M134 Minigun, and M230 chain gun; and a lock-on and simulated firing of the AGM114 Hellfire missile. The MX-10D was also qualified for targeting with a number of missile and rocket systems and the M134 Minigun.

Test data was collected using a variety of methods. Six cameras focused on each weapon recorded fore and aft views during each phase of fire. Accelerometers affixed at critical points on the airframe helped engineers determine weapon frequency impacts on the aircraft and targeting stability. Airborne above YPG was an EO/IR system aboard a Cessna Caravan, plus an MD 500 for additional video recording. YPG provided high-speed ground cameras at the various targets and instrumentation for assessing the accuracy and stability of the aircraft’s laser during missile engagements.

At the conclusion of the in-flight test qualifications, the S-70 returned to the Yuma hangar where it was re-configured — from an armed medium attack helicopter back to a “utility” machine — in just one hour and 40 minutes.

When asked about WESCAM’s takeaway from the project, Jennison said, “We’re able to offer the UH-60 MAWS system for UH-60 operators who want a flyaway kit that allows them to go from utility to shooter in less than six hours, and back to utility in under two hours. Additionally, the lessons learned are also transferrable to other classes of helicopter.”

Retired U.S. Marine Corps General Terrence R. Dake, advisor to the Alliance, stated, “The ability to modify the H-60 with the menu of options we offer with our package makes the MWS extremely versatile. The multi-mission capability that is created increases the usefulness of this workhorse, which is well established around the world. The operational testing we conducted in Yuma proves the concept of a modular weapon system that can be rapidly integrated into an aircraft which enhances its versatility, saving time and money.”

The Mission Adaptable Weapons System (MAWS) and the Modular Weapons System (MWS) for the Black Hawk are, for all intents and purpose, the same in concept, capabilities, and hardware. The two packages were developed and tested with participation from all parties, utilize the same major components, and can be integrated with the same weapon systems. They also offer similar latitude for customization options to suit a customer’s individual needs.

What is distinctive is the way in which the two systems are sourced. MAWS is available exclusively through L-3 WESCAM. The MSW is available through the UH-60 Weaponization Alliance, specifically Stan Wood at Fulcrum Concepts or Brian Reilly at Butler National Corporation.

Alex Anduze is the director of experimental flight test at Firehawk Helicopters and flew the Yuma flight test qualifications. As a former Army UH-60 pilot and a Sikorsky flight test engineer and experimental test pilot for 17 years, he has a great deal of experience with these types of flight test qualifications.

Of the Yuma testing, Anduze said, “I think this program has a great future in the Black Hawk community. There are many foreign governments looking to have an armed aircraft but they don’t want to have an exclusive armed aircraft. They want to use the aircraft in different missions. So I think the concept is great and the way the program, as it was executed, was extremely successful.”

The MH-60M DAP is not the only armed US H-60. Navy SH-60s and MH-60s have been able to launch torpedoes for a long time, and the MH-60 can be loaded with Hellfire missiles.

Does this armed configuration have any impact on component lives?

Absolutely. 810G vibration testing, fatigue, gun pressure testing and a myriad of other tests must be conducted to make sure excess forces aren’t being induced into the airframe or adversely affecting the pilot/crew.

Has it been granted an AWR yet?