Autopilots aren’t new, but there’s something new about autopilots. Garmin recently brought to market an autopilot designed for helicopters – the GFC 600H Flight Control System – and it’s unlike anything that preceded it.

While autopilots have been a common sight on airplanes since the Second World War, their incorporation into the helicopter world has been slower. Two reasons explain the slow penetration of automation into fling-wing operations.

First, helicopters are simply more difficult to stabilize. Our missions also tend to involve more complex tasks than our fixed-wing brethren’s droning in straight lines. Whether hovering, slinging, bucketing, or even just working a tough confined area landing; the helicopter culture still sees its mission as requiring hairy-chested piloting skill, not automation.

Second, integration of a helicopter flight control system (HFCS) into the common mechanical irreversible flight control architecture has typically been complex, owing to the need to mitigate possible failure modes. An autopilot-equipped machine must be safe when everything is working fine, but also safe – or safely recoverable, at least – should the system malfunction. The resulting legacy systems have been complex, heavy and expensive.

I’m reminded of the architecture of the Honeywell autopilot in the Bell 412 that I used to fly: redundant limited-authority high-speed series actuators subject to centering by low-speed parallel actuators, incorporating detent springs and clutches. It worked, but nobody would describe the installation as simple. Garmin had a better idea.

Garmin’s idea in a nutshell: simpler is better. The GFC 600H installation consists of a Garmin GMC 605H mode controller panel, plus a single GFS 83 “smart servo” for each axis. The servos are installed in parallel, meaning that their activity back-drives the cyclic and is perceptible in the pilot’s hand.

An optional, independent yaw axis provides heading hold features in the hover, and this blends into turn coordination in forward flight. The yaw axis uses a clutched variant of the same servo. A potentiometer on the collective provides a calibrated amount of pedal in coordination with power changes; a feedforward strategy that improves performance.

Redundant input data comes from both an attitude/heading reference system (AHRS) integral to the GMC 605H controller, and a remote Garmin AHRS. A Garmin GPS is a prerequisite for installation as a source of position and velocity data, as is a Garmin G500H primary flight display.

In the event of a mechanical jam, the servos incorporate a shear device to allow the pilot to break the controls free. Other system failure modes are anticipated by its “fail passive damping feature,” which disengages the servos into an idle state with some residual damping to minimize “stick jump” upon disengagement.

Getting Started

As Garmin was finalizing the supplemental type certification process for the system in the Airbus AS350 B2/B3 (which was completed in mid-February), Vertical was invited to Garmin’s facility in Salem, Oregon, to test it out.

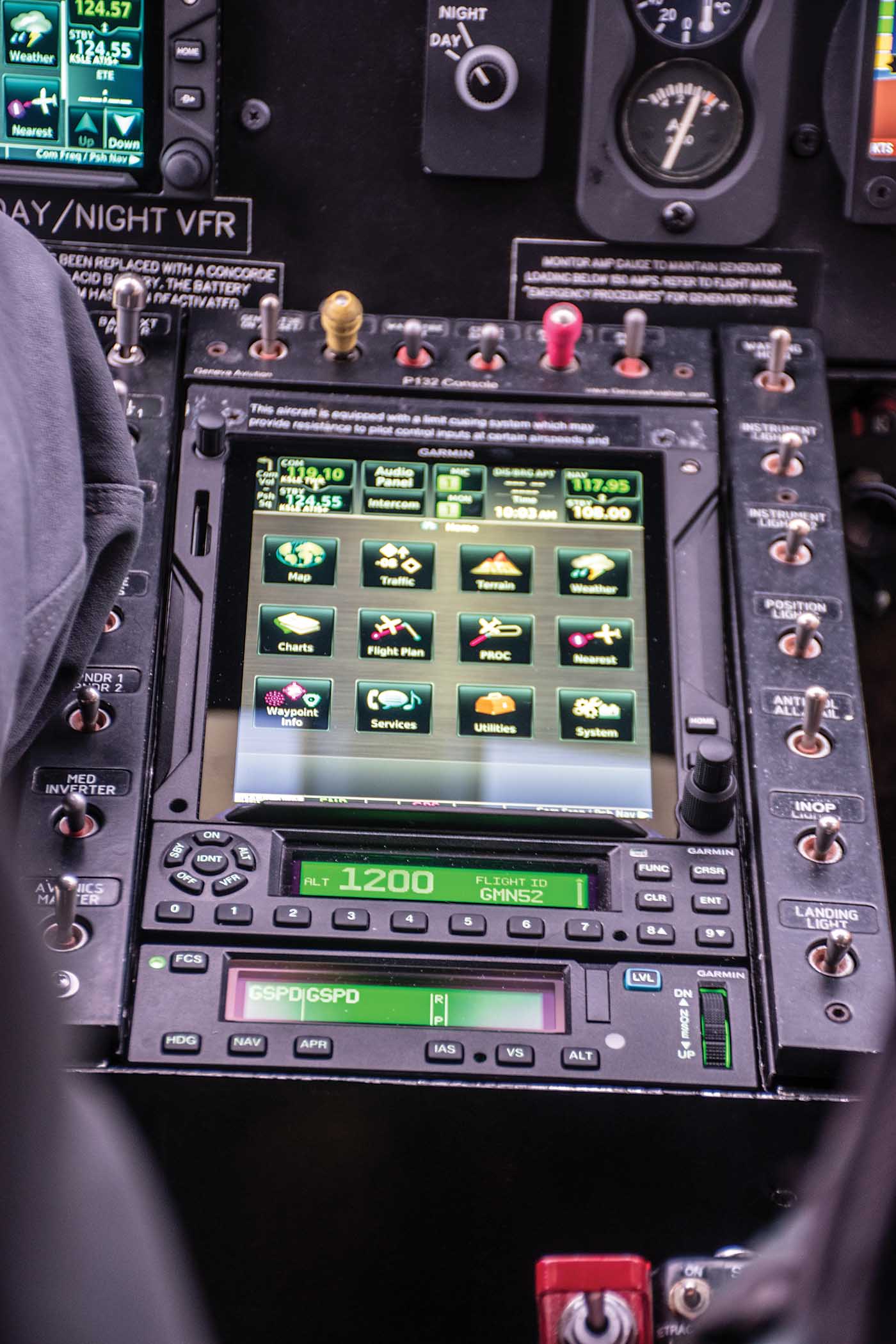

Joining me in the cockpit was Jack Loflin, Garmin’s flight test team leader and developmental test pilot. Loflin led me out to the helipad where an autopilot awaited us with a shiny AS350 B2 AStar (also known as the Squirrel) attached to it. The machine was Garmin’s well-equipped demonstrator, featuring, to no great astonishment, a full suite of Garmin avionics, including the new GTN 750 Xi navigation system.

Once the AS350 was happily whirling, Loflin demonstrated the preflight tests of the autopilot – with one finger. Upon power-up, the system performed its internal built-in test sequence, checking the sensor inputs, processor and actuators. Some status lights flashed, and the cyclic motored through a small range of motion. Loflin needed only press the CONTINUE button, and the FCS disengagement tone signified a happy autopilot.

The interface was simple and conventional. The mode control panel offered pushbutton mode selection, a multifunction control wheel for inputting values such as airspeed or vertical speed, and a night vision goggle (NVG)-compatible display for mode annunciations and warnings. Additionally, mode selections were displayed on the primary flight display.

I’m used to the traditional helicopter autopilot architectures where augmented stability is served in layers: an “SAS” mode for additional vehicle damping, then an attitude retention mode, upon which are piled whatever upper modes are installed, such as position or heading hold functions.

Garmin’s logic is simpler: the autopilot is either engaged or not. The sole autopilot mode applicable in the hover was a blended attitude-and-groundspeed hold mode. The mode, in other words, hovered. The “fly through mode” consisted of grabbing the cyclic and flying the AS350 in the conventional manner. No preliminary steps were required (such as mashing the force trim release) and the presence of the GFC 600H didn’t alter the AS350’s handling or control feel – a feature that greatly simplifies the process of integration and certification.

Gone Hovering

It was a gusty day at Garmin’s facility in Salem, Oregon, with surface winds reported at 13 gusting to 23 knots. In order to baseline the helicopter in the conditions, I elected to start with the autopilot disengaged. I found an unoccupied compass swing pad on the airfield upon which to play, and my efforts to tame the AS350 resulted in a serviceable precision hover within 1.5 feet laterally, about a foot longitudinally and vertically. The workload wasn’t remarkable for a rusty pilot in an unaugmented AS350, typically requiring one’s undivided attention, along with a small cyclic and/or pedal input per second, or so. In addition to the precision hover task, I baselined a lateral sidestep maneuver and a turn around the nose.

I then repeated the tasks with the autopilot engaged. Hands-free, and unassisted by my efforts, the autopilot performed a serviceable hover.

It wasn’t quite as accurate as I had been, especially in the yaw axis where the gusty conditions induced a five or six degree heading wander every few seconds.

The point of the HFCS installation, however, wasn’t to replace me, but rather to augment me. Were I distracted, disoriented, or unable to see through swirling snow or sand, an unpiloted AS350 quickly earns its nickname “Squirrel,” as it departs from stabilized flight. With the GFC 600H engaged however, the gusty conditions simply weren’t in evidence. The helicopter remained upright and gently responsive to disturbances and gusts by holding a selected groundspeed.

Starting from a hover, a change in groundspeed was commanded through the “beep trim” switch on the cyclic, nicely geared at a rate of two knots per “beep.” Loflin kindly pointed out the absence of a groundspeed indication, hinting that it wasn’t integrated, “yet.” I love the way Garmin hints their plans!

Perhaps the best adjective that I could apply to the experience of flying Garmin’s autopilot is “transparent.” With the controls released, a pleasant degree of supplemental stability was conferred upon the AS350, yet remarkably, when I displaced the cyclic I was rewarded with the natural and unmodified handling qualities of the AS350. The combination seemed natural and pleasant.

The Participative Autopilot

While cruising along in level flight, and with Loflin’s concurrence, I simulated a distraction by unwisely checking an incoming text message on my iPhone. Indeed, within a few seconds I had become utterly disoriented – use your imagination! – and the helicopter began to wander from level flight. I decided that the situation was beyond my control, and elected to panic.

Fortunately, Garmin had installed a panic button, in the form of its automatic “Level” function. Depressing the “LVL” button, mounted both on the autopilot control panel and on the cyclic, engaged the autopilot and directed it to capture a nice, sensible level flight attitude. Over the course of multiple trials, the autopilot performed ideally, with a smooth yet decisive intervention. It was an attitude-only response, without airspeed protection, so an alert pilot remains a necessity.

Notwithstanding its merits, the automatic level function still presumes a pilot who is alert and proactive. In my dreams, I want an autopilot that doesn’t just ride along, but will intervene in the interest of our common self-preservation. Garmin apparently thinks so, too, as that describes their Helicopter Electronic Stability & Protection (H-ESP) feature. The autopilot monitors airspeed and bank angle, and like a nervous co-pilot, prompts the pilot in the event of incipient departure from safe conditions.

By way of demonstration, I repeated my earlier simulated distraction, this time with an “inadvertent” nudge of the cyclic. To increase the stakes, I closed my eyes until the autopilot cued a response. Had I been watching, I would have seen the helicopter diverge from level flight. Passing either 45 degrees bank or 13 degrees pitch, I felt the onset of control forces that pushed my hand, and the helicopter, away from further danger.

In addition to monitoring attitude, when the autopilot is engaged it can provide cueing forces in response to incipient underspeed or overspeed conditions.

Force cues are a great idea, but devilishly complicated to implement. Control is imposed by regulating cyclic position, which can be contaminated by transient forces, but I was greatly impressed by the smoothness and proportionality of the force cues. The experience wasn’t like hitting a wall, but rather sensing a force that was clearly inhibiting movement in the “wrong” direction. I sampled flying just outside of the H-ESP envelope, and never found that the cueing forces interfered with cyclic displacement precision. Alternatively, the pilot can depress the FCS DISC button to remove the cueing forces. The experience left no doubt that a helicopter so equipped is a safer machine.

Coupled Modes

Having delivered us from my simulated emergencies, the GFC 600H still had a few tricks to show off. We coupled Heading and Altitude modes, and asked Salem air traffic control for clearance to shoot a few approaches. We were offered approaches to Runway 31, which resulted in an absurd 45 knot tailwind. It proved an ideal test of the system.

Coupled lateral modes include the familiar Heading, Navigation and Approach modes. In the vertical axis, the system would track an airspeed, vertical speed or capture and hold an altitude.

Loflin loaded first the GPS approach procedure and later the ILS procedure, and I watched as the helicopter performed the approaches. The tracking was ideal, even with the flakey winds, and I forgave a slight localizer overshoot during a difficult 110-degree intercept angle. Airspeed management during the approach was within two knots of the commanded value – better than I could have managed under the conditions. More impressive yet, I felt that considering its aggressive striving for precision, the system didn’t sacrifice ride quality; indicative of an autopilot that was well-tuned to the helicopter. The GFC 600H will fly the published missed approach procedure, but the airport was busy enough without us overhead. I broke off visually for the Garmin helipad.

There can be no doubt that automation can make a helicopter both safer and more productive, provided that it’s well integrated. With the GFC 600H, Garmin has a solution that, quite simply, works.